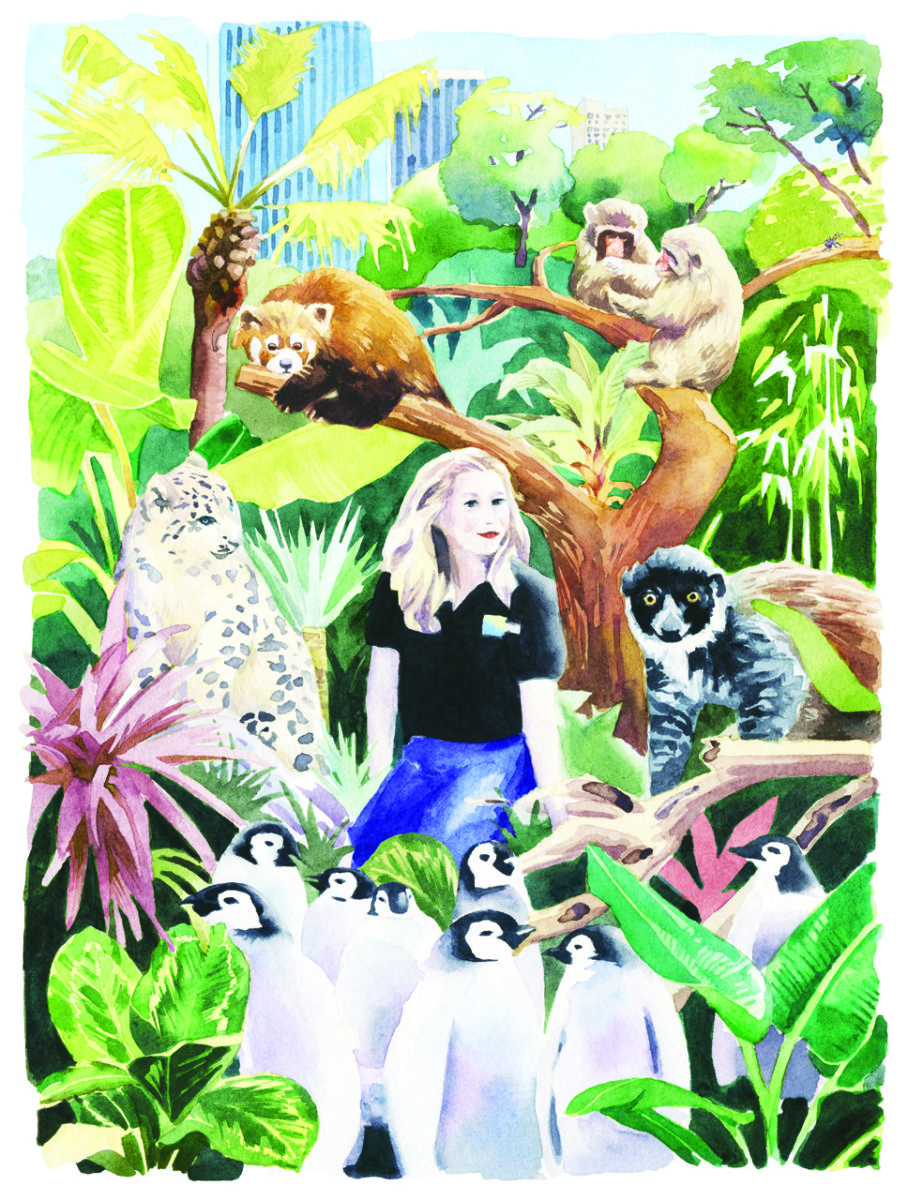

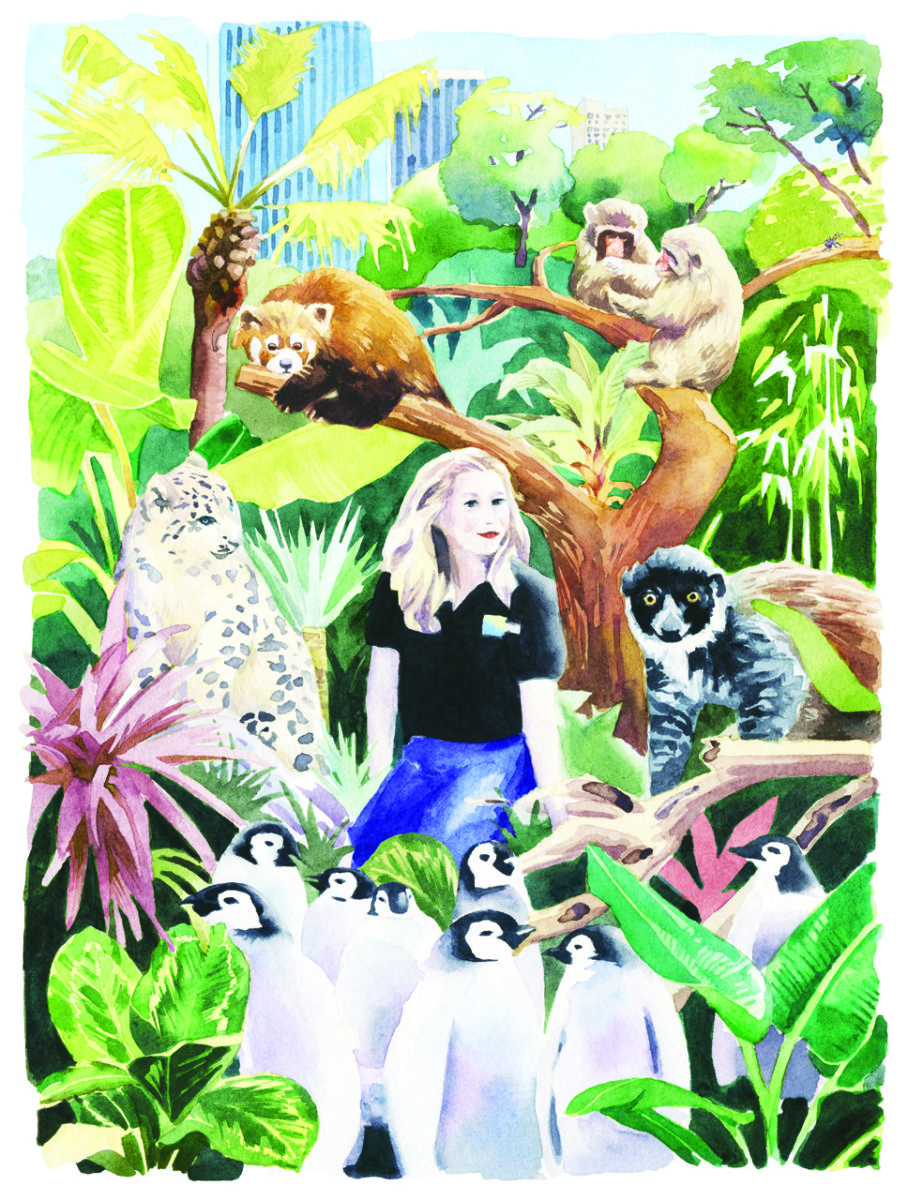

She’s A Keeper

Work is a zoo for Nora Beirne ’08. Literally.

Work is a zoo for Nora Beirne ’08. Literally.

Interview by Ryan Jones

Illustration by Marcel George | Photos Courtesy of Judith Wolfe © Wildlife Conservation Society

I basically have the perfect job. I’m in charge of all the primates and most of the carnivores. We have really cool primates; snow leopards, which are probably my favorite cat; red pandas; mongoose; lemurs—just to mention a few.

Though she graduated with a degree in English, Nora Beirne spends her days hanging with red pandas and endangered snow leopards. A senior keeper at the Central Park Zoo, Beirne talked with us recently about her unlikely career path, the role zoos play in conservation efforts, and what she has in common with Dr. Dolittle.

So how does an English major end up a zookeeper?

A lot of us in the field always had a passion for animals, and not just the normal kid thing of “I want to be a vet.” That wasn’t particularly interesting to me. I started as pre-med at TCNJ at my parent’s request, but realized it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I switched to English because I was good at it. During my junior year, Pat Thomas, the Bronx Zoo’s curator, gave a lecture on campus in which he talked about the research opportunities available to zookeepers. It sounded fascinating. After graduating, I got an apprenticeship at the Turtle Back Zoo. It was paid, full time, full year, and they taught me all the areas of the zoo. After a couple of months I was like, “This is awesome. This is what I want to do.”

A lot of us in the field always had a passion for animals, and not just the normal kid thing of “I want to be a vet.” That wasn’t particularly interesting to me. I started as pre-med at TCNJ at my parent’s request, but realized it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I switched to English because I was good at it. During my junior year, Pat Thomas, the Bronx Zoo’s curator, gave a lecture on campus in which he talked about the research opportunities available to zookeepers. It sounded fascinating. After graduating, I got an apprenticeship at the Turtle Back Zoo. It was paid, full time, full year, and they taught me all the areas of the zoo. After a couple of months I was like, “This is awesome. This is what I want to do.”

How unusual is it for someone without a veterinary or science background to get a chance like that?

It varies. In the field in general, experience counts for a lot. I asked one of the curators at Turtle Back what he looks for in interviews. He said, “A four-year degree, because it shows you can stick with something. After that, what do you do in your spare time? Do you have pets? Do you volunteer at a shelter?” I grew up horseback riding, I’d worked in a stable, and I’d always stayed involved with animals.

What was it like transitioning from animal lover to someone who works with wild animals?

They started me in a less intense area, working with pheasants, sheep, and stuff. I did a lot of self-educating, and there’s also an animal sense that a lot of us have.

How do you mean? Like an intuitive thing?

How do you mean? Like an intuitive thing?

Yes. It’s very bizarre, but I’ve always had it. It’s this ability to read the animals, to see if they look off, if they’re acting unusual. To be able to tell the vet, “I don’t know what it is, but that animal looks off.”

Is it reliable?

I’d say a good 85 percent of the time. Some people might call that bogus, but we’ve discussed it amongst ourselves. Some people just really know their animals. I mean, I’m terrible at math—it’s just not how my mind works—but if I see a snow leopard sitting in the wrong area, I’m like, “What are you doing over there?”

After easing your way into the job at Turtle Back, what came next?

When my apprenticeship was over, they said I could stay on as a relief keeper. I did that for almost a year and a half, and for the last six months, I was the second carnivore keeper. And then I got the opportunity to come to Central Park.

It’s not the biggest zoo, but even so, that must be a dream gig.

It’s insane; I basically have the perfect job. I’m in charge of all the primates and most of the carnivores. We have really cool primates; snow leopards, which are probably my favorite cat; red pandas; mongoose; lemurs—just to mention a few.

What is it about the snow leopards you like so much?

They’re remarkably stunning animals—absolutely gorgeous, but also reclusive and shy. And they’re very intelligent. Working with them, you have a lot of obstacles to overcome. But once you gain their trust, it’s pretty special.

How do you gain the trust of an animal that could easily kill you if it wanted?

My particular passion is training animals, and everything we train them for is to reduce the level of stress. Reading your animal is a big part of training—that, and trust. They see you every day, and you build a rapport with them. Since I started working with our snow leopard, she takes voluntary vaccines and ultrasounds through the fence, she rolls over, she lets us check her teeth. We use only positive reinforcement—rewarding behavior we like and ignoring behavior we don’t like. And then you see the animal have that “ah-ha” moment. There’s so much they can communicate to you that you would never expect them to be able to. That’s why we do it.

What other animal interactions have been particularly memorable?

I had worked in the polar area with our penguins for a while, and just before I became the senior keeper, they pulled me back in there because they wanted to hand-rear one year’s worth of chicks. We had some older birds we

weren’t sure would be able to take care of the young. We had eight hatchlings that year, and for about two months—from as soon as they hatched to when we put them back as adult penguins—I fed and cared for eight baby penguins. They’re still some of the friendliest birds we have.

That approach—working closely with animals as opposed to just showing them off behind cages or glass—is a big change from what zoos used to do, isn’t it?

That really happened in the ’80s. The Wildlife Conservation Society, which runs Central Park, Queens, Bronx, and Prospect Park zoos, and also the New York Aquarium, were forerunners in changing that—the idea that the animals should be in habitats, and that we should be teaching people about them. It’s really about education and optimal animal care.

Is that educational aspect part of your job?

It is. There are a lot of keeper chats that I like to do, and I’ve seen a lot of good come from them. They help clarify what we do—how these animals aren’t taken from the wild.

At Central Park, 99 percent of the time, they’re born in zoos from zoo animals, or occasionally they’re animals that are rescued that wouldn’t have survived in the wild. And the care we take of them—the cats get free-range organic chicken. Even I don’t eat free-range organic chicken.

After being around animals all day, do you have the time—or patience—for a pet?

I do. I have a cat and a snake. The snake is no maintenance, and the cat is the lowest-maintenance animal you can have for high reward.

At the risk of putting you on the spot: Are there any animals you just can’t stand?

Spiders. I can’t deal with them, and when they run out of corners, I just leave.

Posted on January 30, 2016