Ebola Ruined Everything

Michael Lee ’12 planned to stay in Sierra Leone when his Peace Corps assignment ended last August. Instead, he was forced to evacuate in the midst of the worst Ebola epidemic in history. He shared what the experience was like, and why he WANTS to return.

I wanted to do some kind of service after college because I love helping others.

I never had the drive to serve in the military, and I don’t think I have the capacity to do it. My junior year, I heard some former Peace Corps volunteers discussing their experiences in Niger: the difficulties adjusting to a new culture, the horrors of travel, the successes of volunteering. They said it had changed their lives for the better. I decided then that the Peace Corps would be my chance to help the world.

I wrote on my application that I’d serve anywhere. When I received my acceptance letter, it said I was going to Sierra Leone, where English is the de facto official language. I immediately Googled “Where is Sierra Leone?” I didn’t know. Then I learned—civil war, Amistad, blood diamonds. Malaria was there, but it wasn’t a concern. Cholera hadn’t broken out. Neither had Ebola.

I was excited by the opportunity.

Bomotoke, August 2012

During early summer training in Freetown, the capital city, I asked to be placed in the most remote village possible. I figured if I was going to do this, I wanted to go all the way. I was sent to Bomotoke, a village in the country’s southern province, 40 miles from the nearest Peace Corps volunteer.

I taught basic math at Charles Yimbo United Methodist High. It’s a junior secondary school—the equivalent of a U.S. middle school—but I had students as old as 23. Many people there start school late because the country is still recovering from the civil war.

For the first year, the school was functional. We had a principal, I could teach, and we got through a lot. But there was no funding for schools. No one cared for the school. It was dysfunctional. They forced my principal to retire while I was there and didn’t hire a new one. Probably the hardest thing was that I never really got support from anyone in regard to the dysfunctional school situation—but I tried. I tried and I tried.

Growing up, I could look at my grandmother and my parents, all of whom had master’s degrees, and see that education had helped them become successful. But in a village where no one has ever had an education, where no one has ever been successful, it’s hard to say, “Spend your money on education.” Yearly tuition there is about $18, but that’s hard to come by. Those statistics about how most of the world lives on less than a dollar a day? That’s how it works there.

September 2012

Mustapha was a 10-year-old kid in my village who lived with his mom and family. His father lived and worked in another village. Mustapha—Staphi—is a good-looking kid: He’s got big eyes and gets really excited about anything. We’d read books together every day. His primary school was rarely in session, because his teachers didn’t show up for work. But I made him study math every day. He’d come to my school with me and I’d put him in the library with a book where he could practice. When I organized a summer school session, I picked him. He loved it, and he excelled. We started hanging out more, and pretty soon he was always at my house. Then he kind of weaseled into staying over at my house, saying, “I’ll stay here, I’ll sleep on the floor, it’s fine.” Then he just started staying all the time.

Staphi had never been outside a five-mile radius of his village, but I did my best to help him see Sierra Leone beyond those boundaries. We traveled to Bo and Freetown together. He saw cities, cars, nice homes, television. He went swimming at the beach and played soccer on the sand. Before that, he didn’t know that the realities of life in Bomotoke aren’t reality for everyone.

I was like his dad. I bought him notebooks, pens, and pencils. I taught him to swim, and he became a better swimmer than me. For nearly a year, I fed him every day. Sometimes we would go fishing for small crabs to cook. Other times I’d buy a box of macaroni in Freetown and, with grated cheese my father had sent from the States, Staphi and I would fashion an Italian feast with buttered toast. It was delicious.

He soon went from being a kid in ripped clothes who had virtually nothing to a person who helped others. He’d teach other kids to read because I had taught him how. He’d teach them to do math because I had taught him. Sierra Leoneans have a nickname for someone who has an education and money. They’ll call you “big man.” It means you have influence. Staphi became a “big man” in his community, and before long, he wanted everyone to have the same opportunities I had given him.

Summer 2013

It took nearly a year to become fully accepted as a member of my community. I learned Krio and Mende, the languages that most Sierra Leoneans speak. I learned the culture. I took on a leadership position in my village. It was small—only about 200 people—so everyone knew me. I was the only foreigner, the only person with an education. I became a “big man.”

I developed such an appreciation for the culture. It’s a different way of life in Sierra Leone. When someone asks, “How are you?” they really want to know. In America, there’s an unspoken agreement about not interacting with people you don’t know. It’s not like that in Sierra Leone. You get in a car or a transport to go somewhere, and you automatically become family with the people riding with you.

By this point, I expected to stay in Sierra Leone when my Peace Corps service ended and be the principal of a school in a Freetown orphanage. My plan was to get Staphi a spot in my school.

But that was before Ebola ruined everything.

Spring and Summer 2014

We first heard of the outbreak in West Africa in April. It started on the eastern border, near Guinea. We were on the western side, eight miles from the coast. I didn’t fear contracting the disease because the chances were so minimal. But then it was in Liberia. It was surrounding us.

In May it finally broke into Sierra Leone and started devastating—200, 300, 600, 1,000 people dead. Our Peace Corps director kept us updated through emails and text messages, telling us the situation was being monitored. But it was unclear when, or if, we’d be evacuated from the country.

The tipping point for the Peace Corps, I think, was when Sierra Leone’s chief doctor fighting Ebola died from the disease. The Peace Corps had to pull its volunteers out because it was becoming too much of a risk. Airlines were shutting down. There was a chance we’d be stranded there. People were saying it was going to get a lot worse before it got better.

Mustapha and I had planned to spend two weeks traveling to Bo and Freetown. Instead, I received my evacuation notice while visiting a friend in a nearby village. That was July 31. I was ordered to stay there until a car came to pick me up the next day. In Bomotoke, I was given 20 minutes to pack my life into bags.

Anything I couldn’t carry with me I gave to one of the families I had gotten close to—all my clothes, pots, pans, everything. And I had to say goodbye to everyone on top of that. Many of the villagers were out in their fields, farming, so I never saw them before I left.

The hardest part was saying goodbye to Staphi. I looked at him and said, “Staphi, I’m going today.” And he said, “OK, no problem, we’ll go today,” thinking we were going on our trip. And it was awful because I had to explain: “No, I’m going today, and I’m not going to see you again for at least a very long time.” He didn’t show any emotion, but I think he wanted to cry.

New Jersey, Winter 2015

I think about Mustapha every day. I feel comfortable knowing he’s with his family. But there’s no phone or Internet connection to his village, so I haven’t spoken with him since I left. I’ve asked volunteers I know from other organizations who are still in Sierra Leone what the situation is like in Bomotoke. From what I can tell, if there is a good place to be in Sierra Leone, Staphi is there—remote, away from the worst of the outbreak. Unfortunately, he’s not getting an education. Schools throughout the country have been closed since July because of the outbreak. That’s a shame because without an education, Staphi’s prospects for success are slim.

I still hope to go back to Sierra Leone—to take that job as principal—because of the opportunities I could give Staphi, because of the friendship and the love I could give him, and because of the friendships that I have in Sierra Leone to build upon.

I’m in limbo. I don’t know if I feel happiness yet. I go to bed at night now and I’m exhausted, but purely because I am exhausted. In Sierra Leone, I’d go to bed feeling happy-exhausted, feeling I had accomplished something. I’d take stock of the day and think, “That was a good day.”

Everything works out for a reason; I think that’s what’s happening now. You can’t get too down, because it will always get better in the end if you put in a little effort. I had a sign posted in my classroom that read, “Dream big. Be proactive.” If you want something, you have to try to get it. If you try, you’ll get somewhere near it. And somewhere near what you want is a lot better than nowhere near it at all.

Gallery

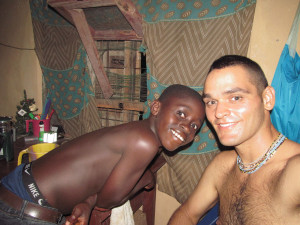

- Mustapha and Lee in Lee’s house in Bomotoke

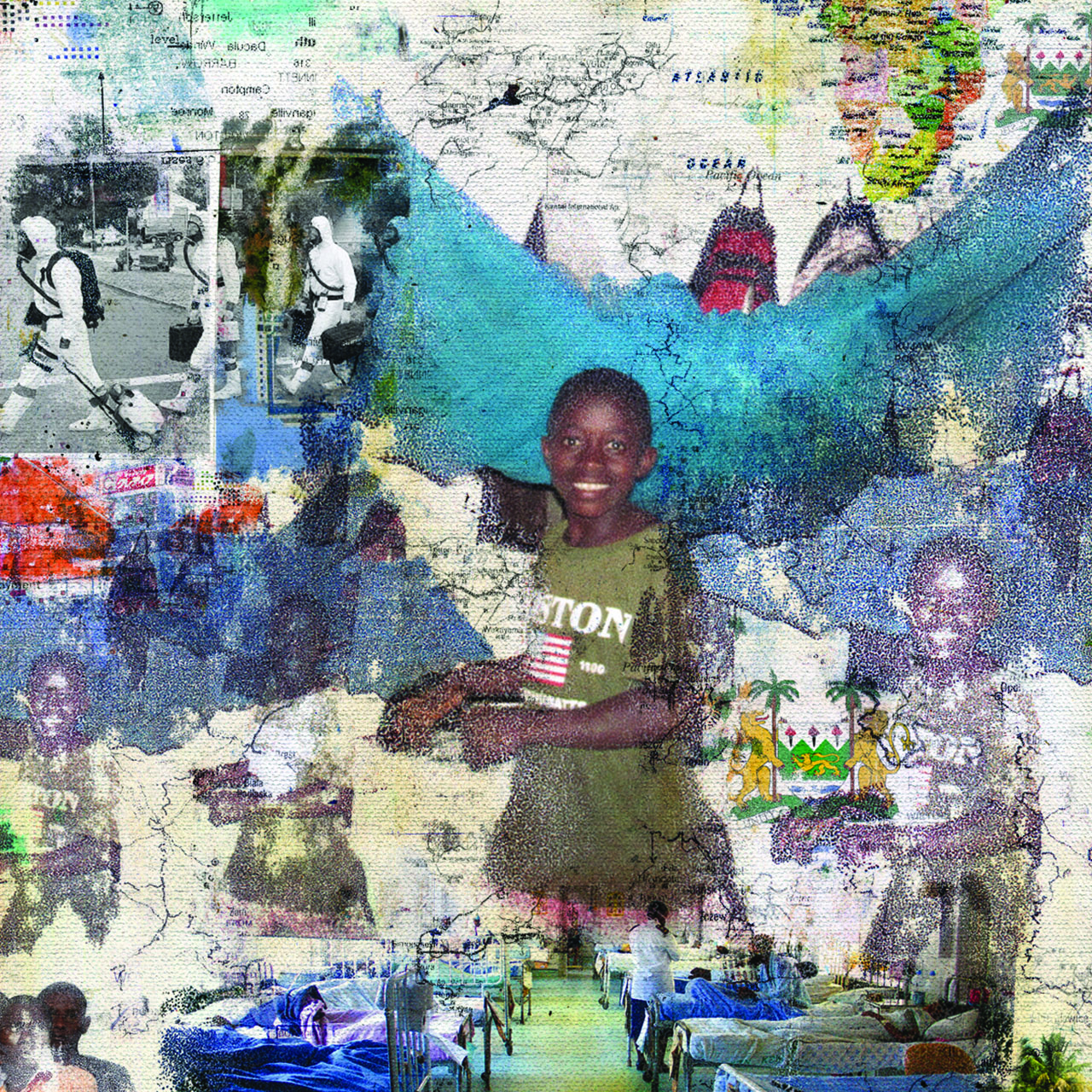

- Lee (foreground) and students in his 2014 summer school session

- Students from Lee’s “Mighty Yellow House” team, which won an interschool track and field competition

- Students and staff from the village school plant a garden in spring 2014

- The road out of Bomotoke as it looked in July 2014, around the time Lee was evacuated

- Two villagers, Jeneba (left) and Jattu, Mustapha’s older sister, shave soap into powder to use when washing clothes in the river.

- The village mosque (left) next to a typical Bomotoke home made of mud and palm leaves

Michael Lee lives in Tinton Falls, New Jersey, and teaches mathematics at Monmouth Regional High School. He is a firefighter in the borough and was recently elected president of the Northside Engine Company.

Dustin Racioppi is a reporter in the state capital for The Record. His writing has also appeared in Drew Magazine and USA Today.

Posted on February 20, 2015