The Lost Angels

Around 1960, a group of stained glass medallions—cut from windows that once provided the backdrop to students bustling in and out of the auditorium on the old Trenton campus—simply vanished. This is the story of those lost artifacts, and how two of them have made their way home.

After a quick glance from behind his paired computer monitors, Taras Pavlovsky, dean of the library, springs up, fans files across the coffee table like an archival croupier and starts to tell a story.

It cuts across genres: It’s a mystery, a history, a whodunit, a parable and a homecoming tale. It’s the story of a few stained glass medallions that vanished more than 60 years ago, and it’s the story of how two of them—works that depicted goddesses modeled on frescoes in the Vatican—made their way home.

It’s been seven months, but Pavlovsky still thrills to discuss the rediscovery. After beating the bushes and chasing dead ends, he had given up hope about 10 years ago. And for Pavlovsky to throw up his hands, the search must have been exhausted indeed. Pavlovsky is not a man easily depleted, let alone deterred.

“You see, I’d spent a long time on this search. It became a quest. Every lead fizzled; the dots refused to connect. But then out of nowhere, these two goddesses just reappear,” Pavlovsky said, eyes brightening behind his wireless glasses. “It’s phenomenal,” he added, with a clap of his hands.

Upon seeing them now, robed women fluttering in a cobalt sky, it is hard to reconcile their grace and fragility with the turmoil of their century. A former music historian and chemical engineer, Pavlovsky’s the sort of man whose excitement feeds on the details, which were first pieced together by Patricia Beaber, the longtime head reference librarian. The story begins more than 100 years ago, when the New Jersey State Normal School was thriving in Trenton, and its present Ewing campus was so much forest and plain.

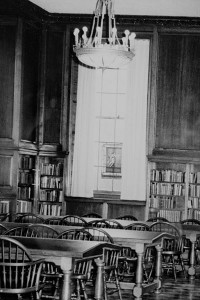

Thirty stained glass windows graced the old auditorium on North Clinton Avenue, constructed in 1894. A couple photographs of the auditorium survive, dimly showing the colored glass on the top sash of the third-floor windows.

They were more than school fixtures; they were presences. Every morning, music played beneath them as the students marched to assembly and every year commencement was held amid their glow.

The windows depicted an array of Muses, personifications of poetry, history, science, religion and other disciplines, as well as Lord Trent’s coat of arms and a host of neoclassical figures. Two of the loveliest images—those ladies likely based on Raphael’s Hours of the Day and Night—glowed on the back wall, in the eighth and twelfth windows.

Graduating classes made a tradition of donating the windows. Alumni of the teacher’s college, then known as the Normal School, as well as of the Model School, a K–12 school run by the Normal School, funded each piece. Although the donations occurred between 1899 and 1914, it is unclear whether the windows were installed sequentially or all at once, and subsequently attributed to the alumni classes.

“Nobody knows exactly when they arrived, but they quickly became a part of the school’s identity,” Pavlovsky said. Before long, it seemed as if they had always been there. And always would be. It was the way they appeared at daybreak and receded every night, almost as part of the natural order. Through decades and upheavals large and small—changing curricula, new college leadership, a world war and the Depression—they went about their business, day after day, transforming light into bodies.

The game is afoot

In early 2005, Beaber, a historian and librarian, chanced upon a 1939 clipping from the State Signal, as the student newspaper was then known. When she read it, her historian antennae gave a telltale tingle.

The article celebrated the addition of stained glass medallions to the library. They had been transplanted from the old auditorium’s beloved windows in Trenton and installed in the new campus, forming a vital bond to the college’s past.

“This restoration project is an attempt to strengthen the links between the old school and new college,” the article said.

Now, more than 65 years later, the college was about to open a new library, and sought to honor its history. Beaber was hooked. She sent the newsprint to Pavlovksy, accompanied by a note.

“Wouldn’t it be nice if one could be located? I had heard of them, but never actually saw one.”

She dived back into the archives and began piecing together a paper trail. There wasn’t much to go on—a few grainy black-and-white photographs, indecipherable minutes from meetings, business correspondence and a few administrative papers—but the game was afoot.

Like a latter-day Holmes and Watson, Pavlovsky and Beaber set out to solve the “Mystery of the Stained Glass Windows.” Their hunt brought them to a shuttered tavern in the small town of Crosswicks, an antiques shop in New Hope, Pennsylvania, and deep into every vault and sub-basement on campus.

Pavlovsky caught a thread. He had honed this talent as a graduate student in musicology at Rutgers University, where he specialized in the paleography of medieval Slavonic chant notation. He loved to pore over disparate sources in search of a shared theme or symbol. Where others saw unrelated smudges, he saw references, intertextual links, allusions. As he cross-referenced the photos and archival records, the outline of a story emerged.

The college moved to the Ewing campus in the mid- 1930s, and the alumni committee was determined not to lose the iconic windows in the process. The committee tapped Mrs. Joseph L. Bodine (nee Gertrude Scudder), the wife of a state Supreme Court Justice and a 1911 graduate of the Model School, to select the best pieces from the abandoned auditorium.

In an even, low-slung cursive, the committee minutes from February 7, 1938, capture Mrs. Bodine’s conclusions: “12 of the windows are unsuitable for further use and should be stored. 18 in the rear have real artistic value. From each one of these, two medallions could be cut for twenty-five dollars apiece.”

The work went to George W. Sotter Studios, of Holicong, Pennsylvania. It seems Sotter and his assistant, Mr. Schmalz, worked on the auditorium windows more or less one at a time (to their chagrin), as funding came in from the alumni. The $25 it cost to cut and rehang the medallions in 1939—still the throes of the Depression—would be more than $425 today.

Sotter started work on the windows in the spring of 1939. On May 13, President Roscoe L. West showed the committee the first medallion, which was to hang in the south window of the conference room in Green Hall.

Beaber tracked down yearbook photos of that first medallion. It adds an upbeat splendor to the scene, where suited men grin and women sit in bobby socks and saddle shoes, skirts smoothed to the knees. It is meant as a backdrop but the goddess takes the limelight, this vague but exuberant figure, robe twisting, torch atop outstretched arm.

A second medallion haunts the yearbooks. Even though the images are dim, the statuesque Greek figure still emits a certain grace and stability. She resembles Athena, with a mace-like object in one hand, an orb or maybe an owl in the other.

Those two are among the six medallions Sotter completed by September 1939. While a few choice windows turned out to be too damaged to use, the work continued sporadically over the next 18 months. Sotter and Schmalz produced at least two more, even while the studio was swamped with commissions from four churches nationwide. Work continued even after Sotter slipped on the ice in the winter of 1940 and broke his leg.

At least eight pieces were made in all, seven of which hung in the main reading room of the library. Feeling that the new campus retained enough of the old Trenton icons, President West wrote Sotter on February 15, 1941, that he was “inclined to think that this [window] is the last one which will be done.”

Spurred by these findings, Pavlovsky contacted old administrators and school officials, and published a summary of the research in this magazine to scare up more information. Faculty recalled seeing the pieces up until 1960 or so, but nobody had a clue as to what became of them. Maybe they were lost during renovations to the library in the 1960s? Maybe they fell apart and were tossed away? No matter the cause, the angels had gone over the brink, into oblivion.

“I was gutted. After making headway in the archives, it seemed that maybe we had a shot at solving the mystery. Then everything just flatlined,” Pavlovsky said with a shrug. “Time swallowed them.”

When the new library opened in October 2005, a larger and bolder replica of the Athena-like image illuminated the landing on the lower level staircase. The inscription underneath reads, “The original window, now lost, was a gift of the graduating Model School class of 1910.”

And that was that.

From oblivion to the inbox

On January 16 of this year, Pavlovsky got an email from the reference desk. It wasn’t something that happened all that often, but the librarian sent this request upward, remembering that years ago Pavlovsky had something to do with old stained glass windows.

He clicked on the email. It had come from someone named George Costantini. A stranger. “As soon as I read that email, I knew, shoot, this guy’s got our windows! There was no question in my mind,” Pavlovsky said. “After scraping myself off the ceiling, I took some deep breaths and contacted George.”

In case it was another bogus lead, Pavlovsky tried to sound nonchalant and disinterested. There was no need; Costantini wasn’t playing games. He had two stained glass angels that his late father had bought sometime in the 1970s.

His father, also named George, had been an avid collector. He had a passion for vintage machinery; he delighted in the combination of industrial heft and handcrafted intricacy, but also collected other artifacts. While clearing out his father’s basement, Costantini unearthed two tightly bound slabs. Inside the foam and plywood sarcophagi lay the angels. They had slumbered all those years among the jumble of steam engines, Civil War memorabilia and fishing rods.

“I hadn’t seen them for 35 years or so,” Costantini said. “They used to hang in my parents’ sunroom, before it was remodeled. My father never said where he picked them up or what they portrayed, but I remembered him mentioning that they came from a school in Trenton.”

Costantini suspected the school in question was the New Jersey School for the Deaf, which had been near their old home, but he took a stab at contacting TCNJ, given its roots in the area.

Pavlovsky and Emily Croll, the director of TCNJ Art Gallery, drove over to meet Costantini at his house in Columbus, south of Trenton.

“When they came here and saw the windows, they were elated,” Costantini remembered. “Taras was grinning from ear to ear. He explained this quest he had been on, this crusade. It was obvious how important the windows were to him, and to the college in general.”

Costantini and his sister Joyce decided to donate the windows, but balked at the paperwork and appraisals required. They wanted a straightforward handover. In the end, they sold the windows to the college for a nominal sum.

“We weren’t in it for the money,” Costantini said. “We felt that the windows belonged back with the school. It was how my father would’ve wanted it, and we were happy to bring about this fairy-tale ending.”

This spring Pavlovsky bumped into Beaber, his old sidekick, at the Lawrenceville farmer’s market. When he told her that two of the medallions had finally been found, she literally jumped for joy, said Pavlovsky.

Roman ruins, a Vatican bath and TCNJ

The euphoria gave way to curiosity for Pavlovsky, as usual. Now that two of the medallions were back, the windows demanded further explanation. A decade ago, he had turned the Internet upside down looking for some clue as to their meaning. Who were these neoclassical figures? What were they holding? He found plenty of information, but now he started looking again. With high-resolution photos of the windows before him and online resources more abundant, he soon hit bull’s-eye.

Michelangelo Maestri, an 18th-century artist, made a career of reproducing Raphael’s work, including his allegorical depictions of the 12 hours of the day and night (the ancient Greeks did not ascribe to a uniform 24-hour day). The recovered windows were of the first and sixth hours of the night, perhaps the most atmospheric images of the series.

In the “First Hour of the Night,” a golden-haired woman in rippling robes hovers against a darkening navy sky, in her hands a flower and an owl. Her head is turned to the owl while a sunlike star—corona, face and all—looks down on her impassively.

This is the Athena-like image that was eventually reproduced for the TCNJ library in 2005. What resembled a mace is a poppy flower, known for its soporific powers, while the owl represents a guardian of the night. The star is Mars, which, according to writer Sarah Hutchins Killikelly, “betokens the many evils that threaten mankind in the night.”

The other window depicts Raphael’s “Sixth Hour of the Night.” It features a bolder, brighter goddess, sporting butterfly wings. She heralds a beacon-like star overhead and cradles a singing swan, the sky blushing pink beneath her pale feet. She “represents the sweet pictures that dreams of early morning bring” and gestures triumphantly toward Mercury, the morning star.

The original two goddesses were among 12 frescoes painted in the Vatican around 1516. The series was stuccoed over long ago, so there is some disagreement about their backdrop. Some say they decorated Cardinal Bibbiena’s bathroom, others the Sala Borgia, but there is a general consensus that they come from Raphael, the master of the High Italian Renaissance.

The aesthetic chain goes back thousands of years. It is believed that Raphael based his goddesses on Roman frescoes. In turn, Michelangelo Maestri and others popularized the frescoes centuries later. Eventually they found form in the Normal School’s windows.

“That’s what makes the history so fascinating. The stained glass images were reproductions of reproductions of reproductions of reproductions,” Pavlovsky said. “They recur through time, without strict beginning or end.”

Brought back to light

In TCNJ’s Art and Interactive Multimedia Building, Croll placed the windows on a table, on a bed of archival sheeting and quilted blue cloth. They lay there, inert and flat, the painted glass holding a dull metallic sheen. Then she raised them upright and, voilà, they turned on. It was a strange alchemy, the instant transformation from base slab to radiant being.

“Initially, I thought they would be pretty pieces of college memorabilia, but once I saw them, I realized of course that they strike a universal chord,” Croll said. “They are beautiful 19th-century works of art.”

Measuring 27.5″ x 19.5″, the pieces are modest compared to other stained glass works. They are not the dazzling rose windows of Chartres or Tiffany’s brilliant pageant, but they still awe. Every stained glass window carries a gleam of the cathedral, a glint of the sacred. And in their way, the goddesses are perfect.

Their images will soon be hung again on campus. There are unanswered questions, but they hardly matter now that the medallions are back. In fact, the mysteries make the pieces even more compelling and meaningful. Things fall apart, time escapes us and the world scatters, but it’s not all disarray. There are recoveries and connections despite the fray. Things come together, after all.

A luminous, anonymous world: An effort to appraise hıstory

A tugboat named Patricia pushed a barge up Newtown Creek, the sludgy channel separating Brooklyn and Queens. It rested outside a blocklong brick building where Mary Clerkin Higgins has her glass studio.

Shelves and cubbies of iridescent glass line the room like troves of dismantled rainbows. On sturdy worktables lie gemlike windows and sheets of tracing paper with elaborate designs. A large stained glass disk from Canterbury Cathedral is under repair, a hard pool of medieval colors in post-industrial Brooklyn.

Higgins, a leading stained glass conservator and artist, knows all too well how difficult it is to solve these historical puzzles. Anonymity abounds in this world of light and color. Paradoxically, the art form keeps the past vibrantly alive even while it hides its own history.

“We’re always happy on the rare occasions that someone has actually signed a work,” Higgins said. “There is still a lot that isn’t known about stained glass, especially in American glass. Scholars are only now starting to put together a comprehensive study of the different studios. Hopefully we’ll end up with a complete compendium.”

The work of 19th-century masters like John LaFarge and Louis Comfort Tiffany is well documented, but they are the exception. For the most part, stained glass artists worked in obscurity. In part, this is due to the fact that they were craftsmen as well as artists—their creations belonged to a utilitarian culture. Provenance was not a priority, especially when so many of the images were reproductions rather than original designs.

Emily Croll, director of TCNJ Art Gallery, recently brought the college’s two recovered windows to Higgins for evaluation. They were in surprisingly good condition—the leading on the frames held fast and the painted center panels kept their color.

“The pieces were the work of a competent artist but not a virtuoso,” Higgins said. “They are surehanded copies of neoclassical images popular at the time.”

The artist started with the lightly tinted glass and painted the figure in dark brown lines. After firing the glass, the background blues and purples were applied in layers and fired at a lower temperature. George Sotter would later frame the image in 12 leaded green rectangles and a yellow border.

Their condition is surprising when you consider what they have endured. Unlike chapel windows, serenely overhead, these pieces contended with more than the usual abuses of storm and sun. These were used. For decades, the auditorium windows slammed open and shut, then the medallions rattled against the windowpanes, hoisted and tilted against the light by admirers, briskly dusted by caretakers.

“Often the greatest damage is inflicted with the best intentions,” Higgins explained. “People will clean windows, give them a wipe and polish without realizing how easily the pigmentation is ruined.” Death by Windex.

It is difficult to precisely date TCNJ’s windows. There are no telltale watermarks or signatures. Unlike other arts, the materials and techniques of stained glass work rarely change, and the images often stayed popular for decades, Higgins said. However, given the neoclassical theme and the fact that paint from the early and mid-19th century tends to break down, the goddesses likely date from around 1880–1910.

The urge to pinpoint origins is understandable, but ultimately the value of the pieces lies in what they signify to the college, not merely how old they are.

“These windows are part of the institutional history and heritage. These are the images they chose at the beginning for their surroundings,” Higgins observed. “These pieces are very much of their time and reflect the aspirations and tastes of the age.”

Posted on September 29, 2014