From Elvis to “Elvira”

Richard Sterban ’62 has shared the stage with “the King” and topped the country charts with his band the Oak Ridge Boys, but one of his favorite music memories took place on campus 50 years ago.

To hear Richard Sterban tell it, he was consistently outperformed by other voice majors at TCNJ, then named Trenton State College. “Sometimes I wondered, ‘Why am I in this class? Listen to the way these other guys are singing.’” Even Sterban’s favorite college memory, going from dorm to dorm singing Christmas carols with his classmates, has him playing a marginal role. He admits, without hesitation, that he was the worst singer of the bunch.

Sterban now possesses a reverberating bass voice recognized by countless country music fans. Even over the telephone, those pipes sound downright biblical. He is still not entirely confident in his abilities. That’s understandable when you’re 18 and unproven, still refining a gift bestowed by the puberty gods five years earlier. But when you’ve sung backup for Elvis Presley? After you served as a legendary country band’s soulful backbone for nearly 40 years? As the source of the memorable chorus—“Giddy up, oom papa oom papa mow mow”—in “Elvira,” 1981’s twangy crossover smash?

“I’ve always been a person that’s been kind of tough on myself, I don’t know why,” says Sterban, 69, who attended TCNJ from 1961 to 1962. “Sometimes, when it comes to singing, self-confidence is a little bit of a problem for me. If you ask me today, I think I’m the worst singer in the Oak Ridge Boys. That’s just the way I am. But, obviously, I can’t be that bad or I wouldn’t have had the career that I’ve had.”

An education interrupted

Whatever his flaws, real or imaginary, Sterban always wanted to perform. The Collingswood (NJ) High School graduate was advised by his guidance counselor and music teacher there that TCNJ had excellent music programs. “I was trying to be realistic at the time: that being successful as a young kid coming out of New Jersey, that it was going to be a long shot at best,” he says. “I felt if I never did make it as a singer, the fact that I could teach music would be a good career for me. It’s something I feel I could have been good at and thrived at.”

One desirable option emerged as a freshman. At a gospel show in Philadelphia, Sterban hit it off with some guys from Bristol, PA. They formed a gospel group, the Keystone Quartet, that was in such demand that Sterban decided to hit the road instead of the books.

Sterban says telling his parents that he was leaving TCNJ was one of the hardest things he’s had to do. The logic behind staying is appropriately self-deprecating: College could have made him a better singer. What he learned in a year—the proper way to breathe, harmony, music theory—still help him today. (The 8 A.M. beginners violin class, where a roomful of novices produced unnatural, unholy sounds? Not so much.) “As I’ve gotten older and reflected on that, I wish I could have stayed longer,” Sterban says. “It would have been a benefit to me if I had.”

If Sterban’s voice had improved, Ken Tucker, the managing editor of Country Weekly magazine, might be dead. “In the late ’80s, I went to one of [the Oaks’] concerts at Ponderosa Park near Salem, Ohio,” recalls Tucker, who sat on the venue’s lawn. “When he sang, my chest vibrated with that bass voice. I’ve never experienced that before or since.”

Tucker says he was between 50 and 75 yards away from the stage.

From Elvis to “Elvira”

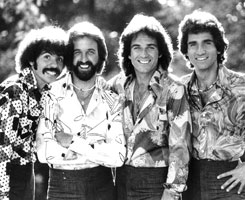

After a lengthy stay with the Keystone Quartet, Sterban moved to the Stamps Quartet, where he performed with Presley for a little over a year. When the Oak Ridge Boys invited Sterban to join their lineup in 1972, the group was nowhere near superstar status. Presley, at one point, even asked him to come back. Though flattered, Sterban declined. “I felt that the Oak Ridge Boys had a great deal of potential,” he says.

Still, Sterban didn’t think the band would become so successful. Enter “Elvira.” Other artists had recorded the song, but the Oaks made it their own, selling more than 2 million records and getting a nation to sing along. The group was established at the time, thanks to 12number one singles. But the “Elvira” phenomenon—an Alaska radio station played the song 72 hours straight—turned the band into “a major name in the music business,” according to Sterban.

“I can picture the recording session in my mind,” he says. “The looks on the musicians’ faces—we used regular Nashville session musicians—they were all smiling, laughing, having a good time. The song went down really easy. We did it in just a couple of takes. It wasn’t hard. We felt pretty good about it.” The band then went on tour. “It was in Spokane, Washington,” Sterban recalls. “Right in the middle of the show, after we had done several of our regular songs and our hits, we just threw it in there. We wanted to try it out. And the reaction of the crowd was unbelievable. I lost track of how many times we had to encore it, but I know it was at least three or four times. Right in the middle of the show, we had to do it over and over again. Then we had to encore it again at the end of the show. The crowd went wild.”

The scene repeated itself until the Oaks urged their record label to immediately release “Elvira” as a single. “It’s still our signature song,” says Sterban, who insists the band has not grown tired of it. Neither have audiences. “When we do that song, even after all these years, people still go crazy,” Sterban says. The song is so popular that the Oak Ridge Boys incorporated it into their beloved Christmas concerts. A few months back, the band appeared on a special hosted by Bill Gaither, the gospel music icon. The event was held on the grounds of the Billy Graham Library in Charlotte, NC. Billy’s son, Franklin, sat in the front row. The Oaks, fresh off recording a gospel album, had appropriate songs at the ready.

“We get out there and everyone is yelling, ‘Do “Elvira!”’ in the middle of this gospel show,” Sterban says. The crowd got what it wanted. “I got up there and did my usual ‘oom papa mow mows,’” he adds. “I just hoped Franklin Graham liked it.”

Down the road

The Oak Ridge Boys have no immediate plans to stop performing. Everyone feels good and still loves what they’re doing. And the demand is there.

“They remain a favorite that can go out on tour and work hard and be relevant,” says Country Weekly’s Tucker. (In March 2011, Entertainment Weekly reported that the band was still “singing good.”) After so much time together, Sterban says the Oaks know it takes four men to create that enduring sound. “We travel on the same bus,” Sterban observes. “It’s amazing how many acts refuse to even ride on the same bus or won’t share the same dressing room. That’s never been the case with us.” He and bandmates Joe Bonsall, William Lee Golden, and Duane Allen have formed “a friendship for each other, a love for each other in a lot of ways.”

Sterban would like any post-Oak Ridge Boys plans to involve baseball, which he consumes in all forms. He raves about The Yankee Years, Joe Torre’s memoir of his time managing the Yankees, and famed sports author John Feinstein’s Living on the Black. He owns both the major and minor league cable packages, so he can watch the Nashville Sounds, the Milwaukee Brewers affiliate that he was once part owner of, while on tour. “I always spend a lot of time paying attention, especially to what the color [commentators] are saying,” Sterban says. “I feel like I have a knack of before they say something, I’m usually thinking it. I’ve been to enough baseball games, I’ve hung out with enough scouts, and I think I’ve learned about the finer aspects,” like why a player isn’t hitting or what’s wrong with a pitcher’s delivery. “I recognize a lot of that stuff. I think I could be good at it. That’s for down the road someday.”

Right now, color commentary is a hobby, and Vanderbilt University’s nonconference games provide an outlet. “He’s got a love and a passion for the sport, and that’s the first thing that you need,” says broadcast partner Eric Jones, who is also the university’s ticket manager. “He is respectful of the way that the game is moving, and he will always kind of defer to my play-by-play.” Jones would like Sterban to get more comfortable. “I’m trying to encourage him to talk more,” he adds. “I don’t have a voice like he does…Sometimes, I look over and my voice is so bad compared to this guy. It is amazing to sit there and listen to him talk in normal conversation. I feel myself staring at him.”

Such praise would have floored the unsure freshman singer who looked at his performing classmates with resigned admiration. Why am I in this class? Listen to the way these other guys are singing. Richard Sterban was right. He didn’t belong at TCNJ. Turns out he’s always belonged behind a microphone.

Posted on March 1, 2012