Then and Now: Baccalaureate Nursing Education at TCNJ

More than a century of awarding only education-related degrees ended with the matriculation of TCNJ’s first baccalaureate-track nursing students in 1966. Here is a brief look at the program’s four decades.

The College’s 111-year history of offering only education-related degrees came to an end in 1966 with the matriculation of the first class of baccalaureate-track nursing students. As the school prepares to celebrate the 40th anniversary of that class’s graduation, we take look at some of the changes that have occurred during TCNJ’s four decades of offering baccalaureate-nursing education.

Barbara Medoff Cooper, Jo Ann Ennis, and Theresa M. Valiga, alumnae from the 40th anniversary class, said the College’s first non-education majors faced several challenges. For starters, TCNJ had no nursing building, no medical library, and the only lab available to nursing students was a makeshift one set up in the Decker Hall basement. “They put a few beds down there, and a few mannequins, so it wasn’t without a completely human look to it,” recalled Ennis about the setup in Decker.

There were also no nursing-specific science classes, Valiga and Medoff-Cooper recalled. Instead, the students in the nursing program enrolled in anatomy and physiology courses that were offered through the biology department. This quickly led to problems when, halfway through the semester, the students complained that they “were still talking about owls” and had yet to discuss human anatomy or physiology, Valiga said. When she and her classmates returned from mid-semester break the following week, they were notified that they were no longer enrolled in the biology department’s Mammalian Physiology course. A new class, Human Physiology, had been quickly established for the soon-to-be nurses. It would meet three times per week for five hours each session so that a semester’s-worth of material could be covered prior to the end of the term. Despite the hectic workload this meant, the students “were thrilled that we were going to actually start talking about human beings,” Valiga remembered.

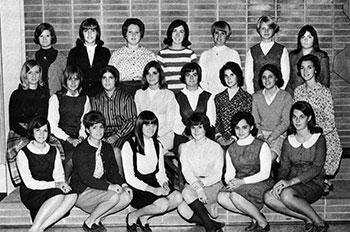

Unlike their counterparts in the education programs, TCNJ’s first nursing students had a strict dress code. “We were the only ones on campus who couldn’t wear jeans to class,” Medoff-Cooper said. The soon-to-be nurses had to wear skirts (slacks were not allowed) to all class meetings. Added Valiga: “This was the mid-1960s and everyone was freaking out and walking around in tie-dye shirts, and here we were in sweaters and skirts,” Valiga remembered. Marian Hosford, the program’s first chairperson, “wanted to make a statement to campus about what the program was—that it was not a typical, technical, do-the-task kind of a program. It had an intellectual and professional component,” Valiga said.

In this vein, Hosford also decided that her baccalaureate-educated nurses would not wear the “traditional” nurses’ uniforms of white caps and white stockings, thus further differentiating them from nurses who were educated in hospital diploma programs. “She really wanted us to be trailblazers,” recalled Medoff-Cooper. The students were given gold lab coats, white blouses, blue skirts, and brown ripple-soled shoes to wear when they left campus for clinical assignments. The students’ reaction to the uniforms was less than enthusiastic. “We were happy we had to leave so early in the morning for clinical,” joked Valiga,” so that none of the other students saw us in the uniforms.”

Ennis recalled that several students in the program (herself included) were disappointed that they wouldn’t be receiving the traditional white nurses’ cap. “We thought at the time that, if you’re going to be a nurse, you’ve got to have a nurse’s cap,” she explained. Hosford eventually relented on this matter, and the students were allowed to design an “official” cap for the program, Valiga said. But looking back now, Ennis realizes that Hosford was right. “She knew that [caps] weren’t going to be a part of a nurses ‘official’ uniform in the future,” Ennis said. “It’s an old-fashioned idea of nursing.” Ennis said her cap sat in a drawer for years until she donated it to the College archives.

The Department of Nursing achieved Division status in 1972, and a year later faculty and students moved into their own building. According to a self-study report authored by Emerita Professor Gladys Word, the division’s move into its own building was an important step in that it helped give “physical campus visibility” to the program. Word’s report also indicated that the mid-1970s saw two important firsts for the nursing division: the program enrolled its first African-American and male students.

In 1980, the Division of Nursing received a charter from Sigma Theta Tau, the nursing honors society. One year later, the division achieved School status. Susan Bakewell-Sachs, the Carol Kuser Loser Dean of what is now called the School of Nursing, Health, and Exercise Science, said that enrollments in the school’s baccalaureate program mirrored national averages, hitting a high in the mid-1980s, declining, and then rebounding since 2000.

By 1997, the program had outgrown the old Nursing Building and moved into Paul Loser Hall.

Curriculum revisions were implemented several times during the program’s history. “Obviously our program is in a constant state of change as necessitated by nursing being a human science,” explained Professor Susan Boughn, who is in her 31st year of teaching at the College. “Nursing faculty constantly revise every aspect of their teaching, including content and process—be that in lectures, laboratories, and clinicals. If we didn’t, our patients and clients would die.”

“The lives of the healthcare-consuming public depend upon nursing programs being highly adaptable and fluid as they respond to an ever-increasing body of knowledge,” Boughn added.

Perhaps one of the biggest curriculum changes coincided with the College-wide academic transformation. For baccalaureate nursing students, transformation brought about an emphasis on computerized simulation as a learning and assessment tool. Loser Hall’s state-of-the-art labs house a family of computer-controlled “Sim patients”—including a Sim woman that goes through labor and delivers a baby. (That’s quite a change from the early days when, Ennis recalled, she and fellow students used oranges to learn how to give injections.)

“Going into a patient’s room for the first time knowing that you’re going to make a physical impact upon their life is an extremely scary prospect” for nursing students, Meghan Farrell ’08 explained. “For me, working in the Sim labs helped prepare me for real-world experiences when dealing with patients [and] gave me confidence.”

One constant during the program’s 40 years has been the emphasis given to clinical experiences. “There is no way to replace students being in live patient-care settings…and a great deal of effort is put into ensuring quality experiences,” Bakewell-Sachs said. Since the program’s inception, students have been required to complete numerous clinical experiences as part of their studies. Today, TCNJ nursing students are placed at sites throughout Mercer, Hunterdon, Middlesex, Burlington, and Bucks Counties, Bakewell-Sachs said.

Bringing things full circle, Ennis, who is the coordinator of childbirth and parent education and a lactation consultant at Capital Health Systems in Trenton, said that almost every semester TCNJ nursing students are assigned to her hospital for clinical assignments.

“I tell them stories about how things were in my day and they’re often amazed,” Ennis said with a laugh.

Posted on February 23, 2010