A Life in Quilts

For one emerita professor, quilting helps tie together a lifetime of thoughts, ideas, work, love, and loss.

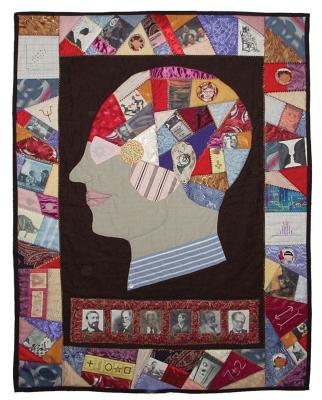

When Nancy Breland’s psychology students would stop by her office for advice or to discuss a difficult paper, their gaze would inevitably gravitate to a quilt hanging on the wall. Scattered on and around a silhouette of a man’s profile on the quilt are smaller images of thinkers and concepts from the history of psychology: headshots of Sigmund Freud, B.F. Skinner, and Ivan Pavlov; a monkey, in reference to a classic study about maternal love; optical illusions; a bottle of Prozac.

The quilt became an “ice breaker” with the students, who would begin to talk about the people and ideas they recognized from their textbooks.

Crazy About Psychology is just one of nearly 300 quilts Breland, who retired in 2006 after 34 years at TCNJ, has made in the past 25 years. In that time if Breland wasn’t teaching psychology or tending to her family, she was weaving her life experiences into the traditional art form.

Known for her use of geometric designs and bold color, Breland’s work has appeared in juried exhibitions, books, and magazines (including American Quilter Magazine). Her original patterns have been published in Quilters Newsletter. Crazy About Psychology, which deviates from her typical style, appeared in three editions of a basic introductory psychology textbook and has been exhibited at the Museum of American Quilter’s Society (also known as the National Quilt Museum) in Paducah, KY.

Breland became hooked on quilting during one of the busiest times of her life: as a young mother with two small children and a full-time job. Although she had enjoyed making crafts as a child, Breland had never tried quilting until her younger daughter, Julia, was born in 1984, and her next-door neighbor in Pennington, NJ, gave her a handmade baby quilt and offered to show her how to stitch one. Before long, Breland had bought quilting books and figured it out as she went along. “I learned by my own mistakes,” says Breland, whose older daughter, Alison, is a psychologist. “I made one and then I wanted to make another and another and another.”

Despite the demands on her time, quilting became a priority. “Quilting really helped me keep my sanity,” says Breland. She quilted every night as a means of relaxing, thinking, and simply getting time to herself. Sometimes all she could squeeze in was 10 minutes. “But it was 10 minutes for me, and you need that,” she says.

The fine work—stitching fabric pieces together by hand, choosing colors and patterns, and figuring out how to make a beautiful whole from the parts—provided a counterweight to her responsibilities in the psychology department. “I was thinking a lot without words. I was thinking color, pattern, and space,” says Breland, who wrote Tricks With Chintz: Using Large Prints to Add New Magic to Traditional Quilt Blocks, published by the American Quilter’s Society in 1994. Quilting also provided a social network of friends outside academia.

Breland, who earned a BA in psychology and education at Lycoming and with her husband, the late Hunter Breland, earned her doctorate in educational psychology at SUNY Buffalo, specialized in psychological measurement and individual differences. At TCNJ, she taught Introductory Psychology and Psychological Testing and served as department chair for two terms during the 1980s. For a couple years before her retirement, she brought her artwork into the classroom, teaching Psychology and Art, which explored visual perception (how people perceive colors and shapes and how artists use that knowledge in their work) and creativity (where it originates and how to measure and encourage it).

Crazy About Psychology is just one of the quilts that brought together her research in psychology and art. Block Design suggests the red and white colored cubes used in the Wechsler and Binet intelligence tests. Relative Size plays with the classical optical illusion found in textbooks in which an item (in this case a button) appears smaller or larger based on the relative size of items surrounding it. Tropical Fish—which first appears like a gathering of little fish before the eye identifies a large fish because it’s brighter—plays with what’s called value differences, a perceptual principal based on a person’s ability to identify shapes by changes in brightness.

Psychology is just one inspiration for her work. Like many artists, Breland draws ideas from the people and world around her—from stars in the sky and autumn leaves to a bowl of soup and the loss of loved ones.

Moon River, for example, was inspired by a family house on one of the Thousand Islands, where the moon sparkles on the St. Lawrence River. Forest Floor looks like its title—with vegetation and rocks sewn onto the fabric in flowing strokes, as if drawn with a needle. Bridge Club Luncheon, appliquéd with plates and utensils, looks like a table set for four complete with place cards for Breland’s aunts and grandmother.

Quilts, including Bridge Club Luncheon, hang on the walls of her house; many are carefully folded and stored in pillowcases, tagged with the titles. Some of her quilts are intended for display, while others are meant for keeping warm on a cold winter’s night. Those she has made for her granddaughter—including one just finished that is covered with bunny rabbits whose ears flop off the quilt—will be well used.

Quilting has helped Breland heal—after Sept. 11 and after the deaths of her parents and most recently her husband. “Quilts can be very good for working through losses,” she says.

After Sept. 11, she made United We Grieve—with images of fire and darkness—which traveled with the American Quilter’s Society exhibit “United We Quilt.” After her father died in 2001, she made A Host of Golden Daffodils—covered with his favorite flower. One of the flower panels has a lone cloud above the daffodil. Her father’s favorite poem—Daffodils by William Wordsworth—appears on one corner of the quilt. “As I sewed I thought of him and I thought of my loss. It was a healing quilt for me,” says Breland, as was the quilt she made of violets to remember her mother.

Soon after her husband died in 2007, she made a quilt and donated it to charity. “A lot of grief was sewn into that,” says Breland, who needed to give that quilt away. She’s not ready to make a quilt about her widowhood that she will keep. “It’s still too raw,” she says. But her quilting—her network of quilting friends and the work itself—has helped her adapt to life without her husband by giving her something to focus on and “feeding my own self.”

With her gentle Border Collie Nellie at her feet, Breland creates her quilts in the studio-living room of her house, on a quiet street in Pennington. Quilting books line shelves and fabrics, organized by color and pattern, fill cabinets and containers. An antique lawyer’s cabinet with drawers that used to hold briefs today makes room for spools of colorful thread, scissors, pencils, and drawing pads. Pinned to her “design wall” is her latest project: a traditional quilt with solid colors and geometric forms that will be entered in a competition next spring for Amish quilts in Lancaster, PA. Today she does nearly all her work on a sewing machine.

After she completes each quilt—which has taken anywhere from a day to five months— she takes a photograph and sends a copy to her close quilting friends who have moved away. In a journal she records the title, date, dimensions, the threads and materials and techniques she used, and the inspiration for the design.

Now that she’s retired, quilting has taken on a larger role in her life. She’s gone back to school to study art. And she continues to lead a quilters group that meets once a month. Several quilts still hang in the offices of colleagues in the psychology department. Last year, a collection of photographs of her quilts was on display in the Social Sciences Building and will be exhibited in the psychology department.

TCNJ holds a special place for Breland: “I still feel very close to [the College].” Each year she attends a presentation to meet the new psychology student awarded a Marshall Smith scholarship, which the family foundation she established in honor of her husband, aunt, and father helps fund.

Although she gives away some of her quilts as gifts—to colleagues, friends, and family—she rarely sells them. It doesn’t feel right. Because so much of her life—her thoughts, ideas, work, love, and loss—are wrapped up in each quilt, she has a hard time parting with them. Says Breland, “There is so much of me in them that I don’t want to let them go.”

Posted on November 30, 2009