“It was like I walked to the edge of a miracle.”

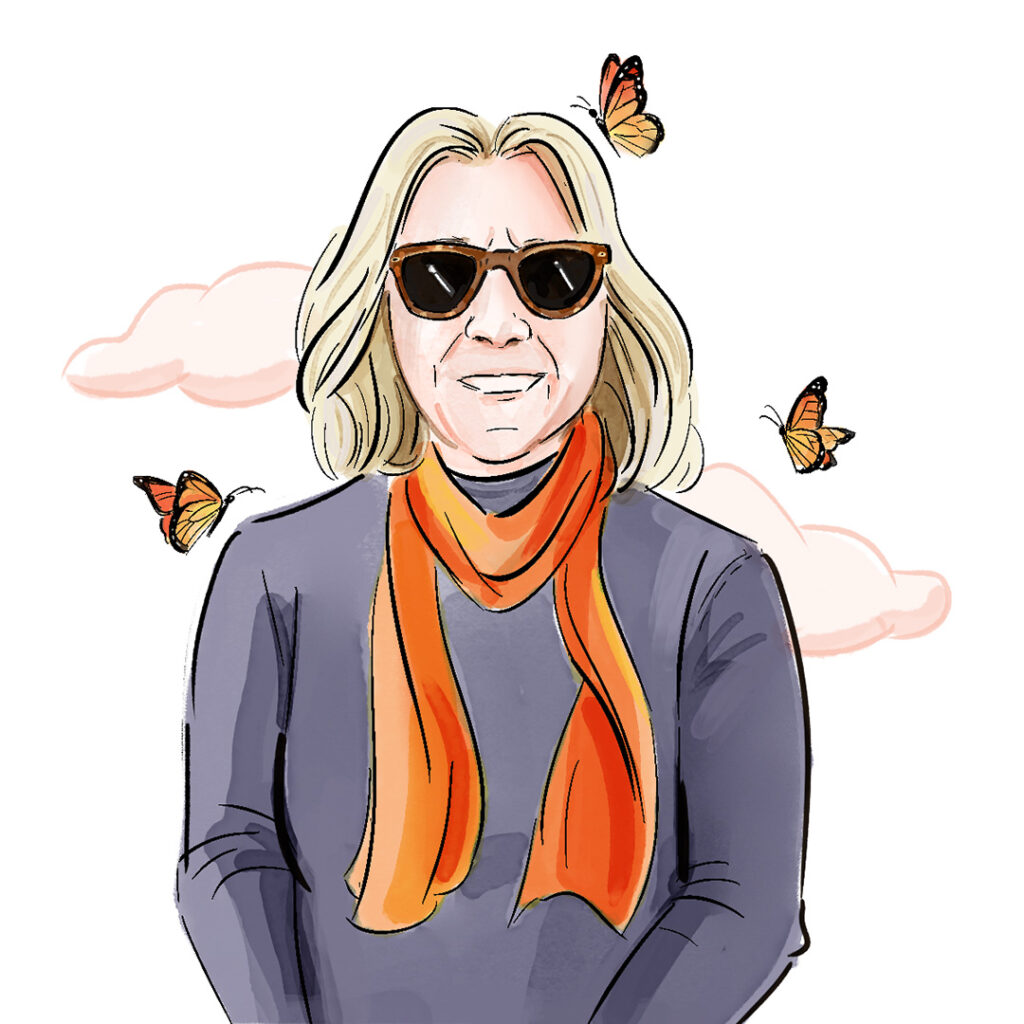

Peggy Campbell-Rush ’76 is all aflutter as she crosses seeing the monarch

butterfly migration off her bucket list.

Monarch butterflies swarm a milkweed plant

“I’ve been intrigued by the monarch butterfly since I was a little girl,” says Peggy Campbell-Rush ’76, remembering late August days in Ship Bottom, New Jersey, when she’d try to catch one of the hundreds that flew around her. What she didn’t know back then was that her childhood wonder placed her in the middle of a natural marvel that she would later come to know intimately: the majestic, yet somewhat mysterious, monarch migration.

Each year, tens of millions of monarch butterflies — with their iconic orange wings and black and white markings —travel a two-way migration over the course of about eight months. First, they spend the summer breeding on milkweed plants throughout the eastern U.S. and Canada. In late August, they journey over 3,000 miles south to the Michoacán mountains of Mexico, where they rest for the winter. Then come spring, they fly north again to start a new breeding season.

Campbell-Rush and other monarch enthusiasts consider the resting period, often referred to as “overwintering,” as the most remarkable stage of the migration. No one knows for sure why or how the monarchs are programmed to come to this particular area, though the temperatures and the natural ecosystem provide perfect conditions for millions of monarchs to congregate in the forest’s oyamel fir trees. Thousands may roost on just a single tree branch. “They cover the entire forest,” says Campbell-Rush. “You can’t see the forest for the butterflies. It’s something I have wanted to experience since I first learned about it.”

Not many people have had the chance to see the spectacle. But thanks to Wish of a Lifetime, an AARP program that helps to keep senior citizens connected to their passions, Campbell-Rush is one of them. “I was reading AARP’s magazine,” she says. “And I saw that they had this Wish of a Lifetime for older people.” Inspired by stories of seniors who followed passions to places like Gettysburg and Ellis Island, she decided to apply.

Campbell-Rush wanted the chance to witness the monarch overwintering to help her convince others of the need to protect these beautiful creatures. A career educator,

Campbell-Rush has taught in New Jersey and Florida and was twice named a New Jersey Teacher of the Year finalist; she’s also a two-time Fulbright Education Fellow. She’s wowed her elementary students with hands-on learning experiences. A favorite lesson was to teach the life cycle of butterflies. She’d bring chrysalises to the classroom so students could watch caterpillars turn to butterflies. It was a lesson in conservation, too. Monarchs are a threatened species due to a number of factors, including deforestation in Mexico and the overuse of pesticides in the U.S. that kill the milkweed, a crucial food source and a breeding ground for the monarchs. She encourages students and neighbors alike to plant milkweed; her own garden, filled with milkweed, is registered as a Monarch Waystation for the migration.

Her wish was granted. In February 2025, she set out on an expedition to see the monarch migration through the World Wildlife Foundation and National Habitat Adventures. “The goal of the trip was to learn more about the monarchs and come back and educate others,” she says.

Campbell-Rush’s trek to the Michoacán mountains was as arduous as that of the butterflies she was about to study. First there was a spirited send-off from preschoolers donned in butterfly wings at the Riverside Presbyterian Day School in Jacksonville, Florida, where Campbell-Rush serves as the Early Learning Center coordinator. Then it was a series of planes, buses, and pick-up trucks to get from Mexico City and ultimately to the foot of the El Rosario Sanctuary, a protected area where the monarchs spend winters. “We rode horses straight up the mountains to about 11,000 feet,” says Campbell-Rush. A final 30-minute hike got her to a clearing in the sanctuary, revealing millions of butterflies. “It was this eureka moment. It was like I walked to the edge of a miracle,” she says. “I just knelt down because it was so amazing.”

She spent the next three days immersed, quite literally, in monarchs. “They land on you,” she says. “But you can’t touch them. You have to just stay still until they’re ready to leave you.” In fact, much of her time in the sanctuary was quiet introspection while listening to the sounds of wings flapping. “It’s a hibernation of sorts for the butterflies, but they aren’t inactive,” she says. “They fly to streams to drink. They keep their wings open for warmth from the sun.” At night, there were lectures from entomologist and adventure leader Court Whelan, author of The Monarch Migration: A Journey through the Monarch Butterfly’s Winter Home. He calls the monarch’s migratory pattern one of the most highly evolved of any species: “When it comes down to the impressiveness of a species, this takes the cake.”

Back home, Campbell-Rush is eager to talk to anyone about her trip who will listen. She’s brought her photos to assemblies at elementary schools and to community centers. She urges people to plant milkweed and delights in the fact that, by mid-March, she had already seen a monarch fluttering in her backyard garden. It’s not an impossibility that it was one she saw in Mexico. “I hope a whole new generation will love and appreciate the monarchs as I do,” she says. “I get to spread the magic.”

Illustrations: Vivian Shih

Posted on June 4, 2025