Opportunity Calls

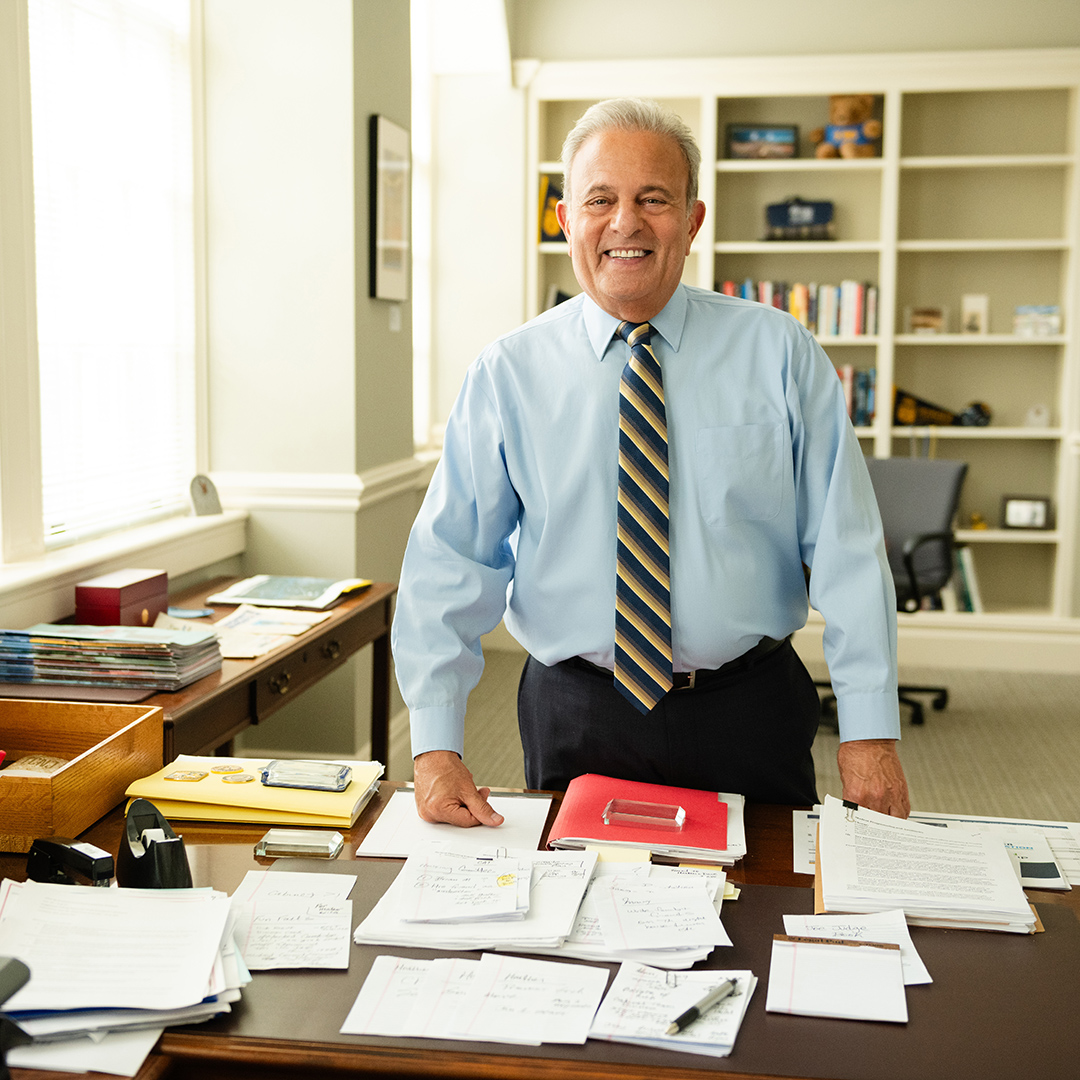

Michael A. Bernstein gets down to business as the college’s 17th president.

President Michael Bernstein

When Michael Bernstein accepted the role of TCNJ’s 17th president on June 6, 2024, he knew he would be leading through difficult times. Nationwide, colleges and universities are facing multiple challenges.

With an economics background, a long career in education, and a year as interim president at TCNJ under his belt, Bernstein is well positioned to help us navigate the future. He has been tested before. As provost and senior vice president at Tulane University in New Orleans, he helped lead the university’s recovery from the emotional and physical devastation of Hurricane Katrina. He also steered Long Island’s Stony Brook University through the taxing unknowns of the pandemic’s early months as its interim president.

Drawn to TCNJ because of its strong academic reputation, Bernstein quickly took pride in our students’ successes. He knows the hallmark of this place is its excellence and he embraces the opportunity to sustain it. Yet, he also knows there is work to do.

Here, Bernstein explains the key headwinds confronting higher education today, especially those schools in the public sector, and shares some plans for our college to manage them.

A Snapshot of Higher Ed Today in Four Graphs

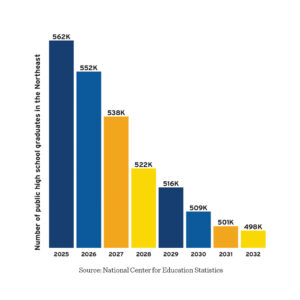

1. The Demographic Cliff

In the second half of this decade, the overall number of college-age Americans will steadily decline. This drop will be especially pronounced in New Jersey and other Northeastern states, from which TCNJ traditionally draws its students.

BERNSTEIN: The good news is, in the immediate term, demand for admission to TCNJ remains strong — we do not have empty seats at present — and we have an excellent brand. We also have a clear-eyed conception of what our challenges are. We are speaking honestly and transparently about them, and we have a sense of what we now need to do. In all these respects, we’re facing our future from a position of strength

Of course, we’re not taking anything for granted. Continuing to execute our mission when the student population is shrinking requires us to move beyond and add to our traditional marketThis new audience is populated with returning students (who had previously interrupted their education), part-time students, older students, students who don’t necessarily want to earn a degree but want a certificate or credential, and also students who might want a postgraduate degree. To be sure, I do think we will remain a top choice for undergraduates in the years ahead, but it is not realistic to think that’s the only thing we need to do to continue to flourish.

2. A Decline in State Funding

Public colleges used to be able to count on the state for a large portion of their annual operating budgets. Over the past 25 years, however, appropriations for higher education have declined in the vast majority of states, New Jersey included. That has forced public colleges and universities to rely more heavily on tuition revenue and incur more debt as they invest in critical needs.

BERNSTEIN: In 1990, the state provided 63% of our funding. Today, that number is about 25%. There’s a close correlation between that decline over the past several decades and the increase in our tuition. We’ve done our best to hold the line on costs, often making difficult choices between, say, investing in scholarships or the wraparound services our students need, like additional counseling, tutoring, and mentoring, or, whether to proceed with or delay meeting critical facility needs, whether they be renovations of labs and classrooms, studios and performance spaces, athletics venues, or residence halls.

As we get leaner and leaner, we still have to function well. Right now, we’re in the midst of a multiyear project to replace the nearly hundred-year-old steam piping that we use to heat the campus. Our business and nursing programs need more space. We need to invest in our campus housing. These projects cost millions and millions of dollars. When we have to borrow, debt service takes up more of our budget, which then leaves less to spend on instruction and student aid.

Remarkably, despite the budget constraints, we continue to deliver exceptional outcomes. We have a 75% four-year graduation rate. That’s the highest in New Jersey among public institutions, the second best in the state overall, and ninth in the country. Ninetytwo percent of our first-year students return. We have alumni leading top businesses and in prestigious graduate schools. The question is, how long can we continue to do more with less? It is simply nonsensical to think TCNJ can continue to deliver exceptional educational outcomes without an increase in available resources. This past year, one public official told me that it was hard to believe the college needed more support given the excellent job it was doing. Frankly, the comment left me speechless. I understand the state’s budget is dramatically squeezed. Nevertheless, it is remarkably shortsighted to undermine the contributions TCNJ makes to New Jersey. In what sector of the economy would the rational response to strong outcomes and results be a reduction in investment and support?

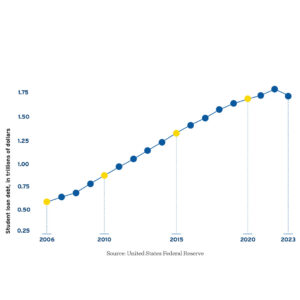

3. Mounting Student Debt

U.S. student debt has doubled over the last two decades, and it now outpaces most other types of consumer borrowing. Colleges, prioritizing affordability, are trying to hold the line on tuition increases and are also putting more money into aid. The flip side, however, is limited revenue growth and additional expense.

BERNSTEIN: We’re very sensitive to the burdens our students and families take on to attend TCNJ. It’s been a major commitment on the part of the institution to keep the education we provide affordable. Since the 2016–17 school year, we’ve more than doubled the amount of institutional merit- and need-based aid to our students. Assuming you believe in the value of a college education, something has to give. Nothing that we do is free. And in fact, the costs of what we do just go up. In some cases, they go up for reasons beyond our control — utilities and supplies become increasingly expensive and, of course, attracting and retaining excellent personnel requires the provisioning of competitive salaries and benefits. Even so, in some cases, our costs are being driven by decisions that are made beyond this campus — many of them in Trenton, some of them in Washington. Rarely do new government mandates and regulatory requirements come paired with the dollars attached to fund them.

Fundamentally, the solution on one level is growing student aid. Clearly, we will need to make scholarship fundraising one of the highest priorities in our advancement efforts for many years to come.

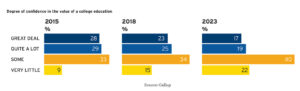

4. Declining Public Confidence in Higher Education

More and more people are starting to question the importance of a college degree. With low unemployment, the availability of free online courses that might teach you what you need to know on a job, and the rising costs of the traditional college experience, a greater percentage of young adults is choosing to enter the work world directly from high school.

BERNSTEIN: It’s perfectly understandable when something is more and more expensive for people to question its value. And indeed, the whole idea of publicly funded higher education was that the public would never be put in the position of having to question the relative value of the experience. All that being said, there are nevertheless an array of misconceptions today regarding the intrinsic value of a higher education degree.

Has that value actually declined? Absolutely not. That’s worth repeating: The value of a college degree has NOT declined. All of the data are completely clear on this: The more degrees you earn, the higher your lifetime earnings. Viewed in this way, it is not surprising to note that a bachelor’s degree is probably the single most powerful tool we have in this country to leverage socioeconomic mobility. Bar none.

I might add — with higher incomes, the data also indicate communities tend to have improved health, longevity, resilience, and solidarity. And, needless to say, communities that are better off also generate higher tax revenues for state and local governments, public services, and K–12 schools. Overall, the higher the proportion of a population holding advanced degrees, the better off that community is.

For all these reasons, it’s vitally important we speak honestly and clearly about what’s distinctive about a TCNJ education. If a student wants to get a certificate or credential in a special skill, there are training courses, many of them online, for that. That’s great. That’s training for a job. And indeed, that is something TCNJ can and should do in certain fields. At the same time, when it comes to our full-time undergraduate programs, we are offering an exceptional experience that provides expertise (in a particular major) along with something else — the preparation for impact and leadership.

Training for leadership is different from training for a job — it involves the cultivation of an array of skills for things like interpersonal and organizational communication, effective team-building and stewardship, along with outstanding instincts for discernment, analysis, and judgment. This is not better than skills-based training for credentials and licenses. It is different.

Leadership is not about a position (although it may often be represented as such); it is about an attitude and an approach to one’s career. It involves making a difference and showing the way. Of course, here at TCNJ, we want all our students to do well when they graduate. But most of all, we want them to do good — to be, in whatever path they pursue, exemplars and inspirations to others.

Bernstein’s Four Priorities to Ensure TCNJ Thrives

1. Innovation

BERNSTEIN: We’ve got to be taking all necessary steps to remain an institution of distinction. Ensuring the quality of the education we offer does not mean simply following the latest trends and best practices in higher education; it means helping to define them, being a peer leader in our sector.

Needs and trends are constantly changing. Higher education looks very different today than it did 20 years ago. Twenty years from now, it will look very different than it does today. We’ve got to be thinking about the needs of future generations of students and constantly innovating. That’s something this institution has always done exceptionally well.

We are being very forward-looking in this respect. Last spring, as part of an initiative I’ve dubbed the LIONS Plan, we had a working group looking at ways to offer a bachelor’s degree in three years. This is something that I believe will become increasingly attractive to and, dare I say, expected by future generations of students. We’ve identified three models that we’re currently exploring.

A second working group developed a business plan for a new School of Graduate, Global, and Online Education that will be positioned to meet the educational needs of some of the new audiences I mentioned earlier. Its first offering, an online master’s degree in clinical mental health counseling, is designed to train a diverse group of clinicians and alleviate service gaps in underserved communities. The program launched this fall with a full class (and a waiting list).

2. Sustainability

BERNSTEIN: Given the headwinds facing the higher ed sector, it should be no surprise that our resources are squeezed. As institutional stewards, we have the obligation to ensure that our budget is sustainable, and we’re focused on that. Last spring, several LIONS Plan working groups spent the semester identifying savings and sources of new revenue. The good news is we are on the right path, but we have a lot of work to do to stay there. This involves reducing our investment in some areas and focusing scarce resources where they will achieve maximum effect.

Some of the initiatives we now pursue, by the way, won’t save us money — but they will save students time. For example, I have pushed very hard for us to go to a 30-unit degree (the equivalent of 120 credits at other institutions) down from the current 32. This will allow us to be more competitive and efficient in the marketplace, as virtually all of our competitors now offer 30-unit diplomas. That’s what our students want and need.

3. Advocacy

BERNSTEIN: TCNJ occupies a vital spot in the New Jersey higher education landscape, providing Garden State families an education that is every bit as excellent as much higher priced, out-of-state colleges. Students who study here stay here. Ninety percent of our last five graduating classes, in fact, have remained in New Jersey, which is a real benefit to the state and its economy. We need to be aggressive in making that point with our elected officials, who are making funding decisions.

Finally, when it comes to communications, our college needs to emphasize the singularly important contribution we make in affording educational opportunities to the underrepresented and underserved people of our state and region. Our exceptionally high graduation rates mean that we deliver, on time and at the lowest possible expense, bachelor’s degrees of extraordinary quality to all our students. We will, of course, always strive to enhance the diversity and inclusive excellence of our student body. Our commitment to equity and educational virtuosity requires that. At the same time, we should always note that TCNJ, better than any other public institution in all of New Jersey, delivers a successful degree outcome on time for all its students.

4. Advancement

BERNSTEIN: TCNJ should have an endowment and yearly volume of current-use funds provided by gifts befitting an institution of our quality. I hope to inculcate a deeply ingrained culture of giving among all the constituencies of our college.

In terms of fundraising priorities, our top-ranked focus should be on scholarship funds. There’s never too much we can do in the arena of accumulating resources that will allow us to ensure the best students have the opportunity to come to our college. We must do whatever we can to attract them here and make it possible for them to attend TCNJ. In addition, we should work to secure resources that enable us to attract and retain the best faculty and staff — raising funds, for example, to create professorships and endowed chairs, and to sustain instructional and mentoring programs across our campus.

There are three things alumni can do to help: First, obviously, give as you are able. It is not an understatement to say philanthropy is life-changing for our students and transformational for our faculty and staff. Second, get others to give, whether they’re alumni or not. And then third, spread the word. You received an excellent education here. You’ve had success. Tell that story far and wide. And often.

Posted on September 15, 2024