Believe it or not!

Two professors speak the truth about the enduring allure of conspiracy theories.

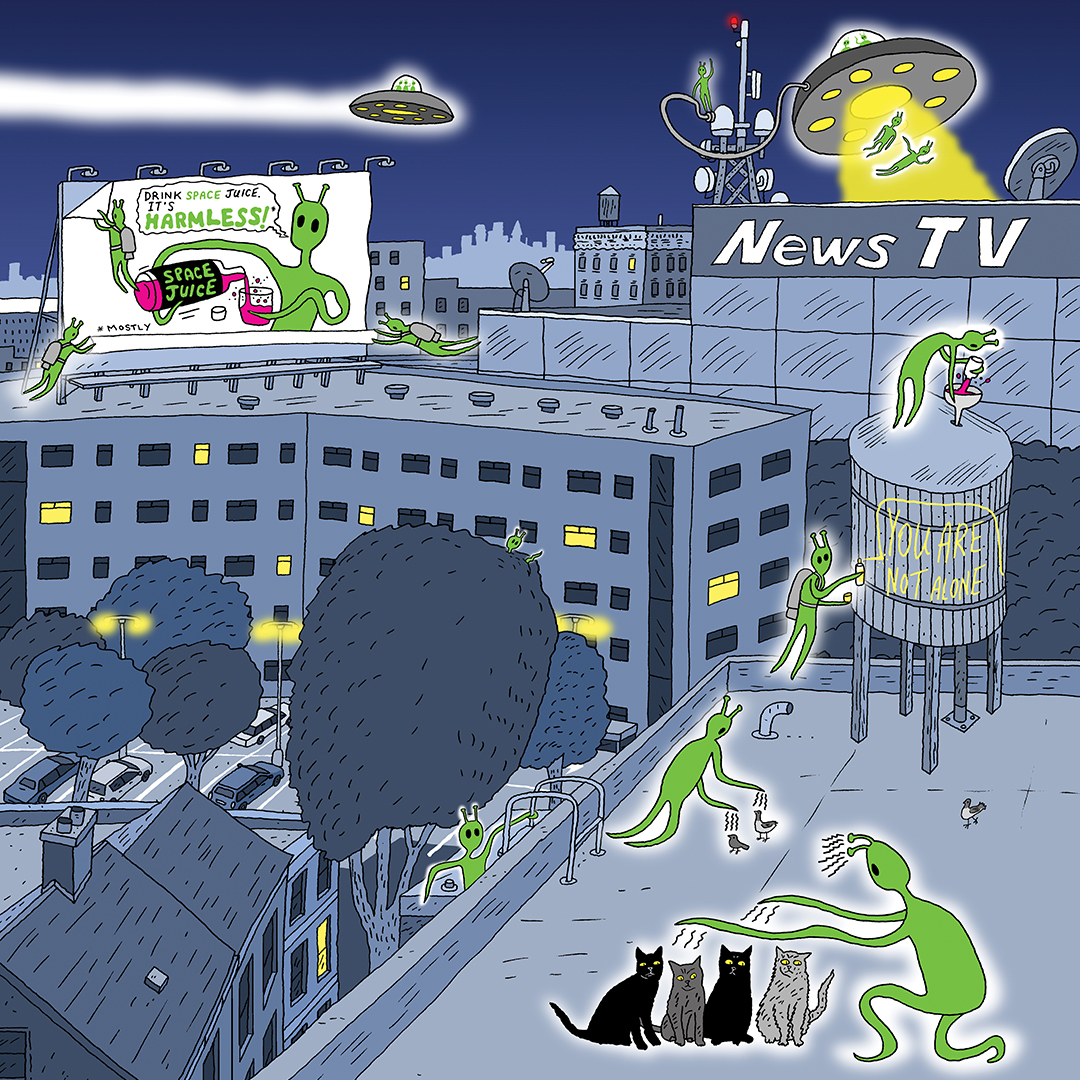

Hoodies up, “students” slink across the TCNJ campus to Forcina Hall, and when no one is looking, duck into a utility closet that doubles as a secret portal to a laboratory deep underground. There, a shape-shifting alien reptile known aboveground as “Tom Arndt” injects microchips into their bloodstreams to program them for their next mission: working as crisis actors in a staged catastrophe that will dominate American politics for as many news cycles as possible.

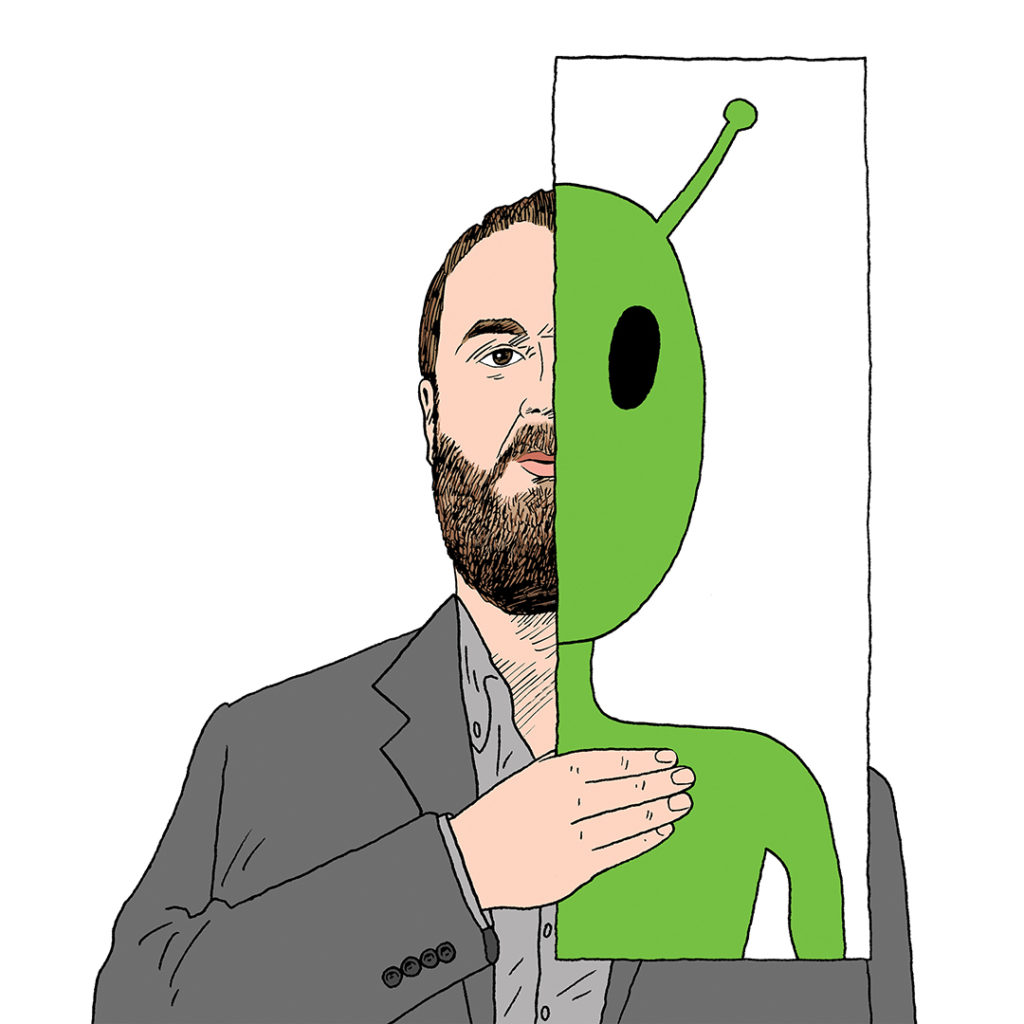

Yeah, none of that is actually happening. But in case anyone feels inclined to take those assertions as fact: Well, OK, there is a Tom Arndt, but he’s a genial adjunct professor of political science without any outward sign of space lizard in his genes. His course, “Conspiracy Theory in American Culture and Politics,” does meet in Forcina, though in a second-floor classroom. And its aim is to get to the root of conspiracy theories, not to serve as the basis for one.

“One thing that motivates me is I’m very anti-conspiratorial,” says Arndt. “I don’t believe any conspiracy theories, and actually find them very toxic, very corrosive, and damaging.”

Arndt is one of two TCNJ instructors who teach classes that examine the phenomenon of conspiracy theories: how they originate, spread, and destabilize not only your Thanksgiving dinners but, increasingly, America’s civic life.

He meets the topic head-on, deconstructing numerous narratives around historic events, including what he calls “the big three” of the last 70 years: the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy; the alleged fakery of the Apollo moon landings; and the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on American soil.

“I’ve identified at least 18 specific story lines that speak to what allegedly happened on 9/11,” says Ardnt. Among them: an easily refuted claim that BBC News “reported” the collapse of 7 World Trade Center before it happened, used to bolster another conspiracy theory claiming that a “controlled demolition” was orchestrated by any number of shady actors.

In nearby Kendall Hall, communication studies professor Paul D’Angelo takes a different approach, providing students with a framework for navigating the intersection of politics, traditional journalism, and social media in a class titled “News in Our Lives Today.”

In trying to determine where a report falls on the continuum from truth to lies and propaganda, look for intent, D’Angelo tells students. Does the author attempt to verify information with named sources? Appear willing to debunk false information? Or is he or she out to “construct a worldview impervious to validation?

“In the best of circumstances, mainstream news is where conspiracy theories should go to die,” D’Angelo tells the class. But that doesn’t always happen, “because people who believe conspiracies are apt to blame the mainstream media for undermining their conspiratorial thoughts. So now ‘the media’ becomes part of the populist rant.”

What’s a conspiracy theory? According to D’Angelo, it’s an “explanation of an event or set of issues that challenges established accounts, and instead refers to the machinations of powerful actors or secret societies” as those responsible, almost always implicating mainstream media as a player.

Conjuring conspiracies to explain events is “kind of attached to our history, our culture,” says Eric Bridgewater, a student in Arndt’s class last fall. Conspiracies “give people the power of narration.”

Bridgewater, a five-year Army veteran, admitted he wasn’t thinking much about conspiracy theories before he took Arndt’s class. But he quickly got into it. He was particularly engaged by speculation about a man holding open an umbrella in the sunshine of Dealey Plaza when JFK was shot, though he was not convinced the guy had any role in the assassination.

Neither was Arndt. In interviews and in class, both he and D’Angelo acknowledged personal antipathy to many prevailing conspiracy theories, but say they attempt to strike a balance. For one thing, says D’Angelo, “the line between when misinformation becomes disinformation is not always that clear. It’s hard to know.”

Arndt says he is transparent with students about his skepticism. “I tell them on the first night of class that I have my mind made up on most of these topics and that I am the furthest thing from a conspiracy theorist,” he says. “But I don’t judge students or grade them unfairly if they happen to buy into any particular theory. Students are always encouraged to bring out their true opinions even if they clash with my own.”

Historically, false and often bizarre narratives aren’t a new development in America or elsewhere, say both professors. But things started getting out of this world in 1947, when a rancher discovered some strange wreckage in the desert near Roswell, New Mexico. Whole industries of entertainment and political intrigue followed, none of it to cash in on the official explanation: a crashed weather balloon.

Aliens are not uncommon figures in the literature. Arndt’s class spent some time looking into the work of David Icke, an Englishman who has posited that many of the world’s powerful elites are actually shape-shifting reptilians from outer space, and also, Jewish.

Today, online, you can buy a create-your-own-conspiracy-theory set of refrigerator magnets, complete with a tin foil hat. Still, public derision of woo-woo apparently does little to curb the bottomless appetite for it. So who believes this stuff? D’Angelo, treading carefully, says that studies show it’s people with relatively lower “news literacy” scores, “and yeah, it does tend to thrive more on the right, obviously, than the left.”

The problem, of course, is that the embrace can turn dangerous. Take Pizzagate, the narrative that posited Hillary Clinton and a cabal of loyalists were sexually abusing children in the basement of Comet Ping Pong, a Washington, D.C., pizzeria. Never mind that the business didn’t have a basement. A North Carolina man took the story to heart and used a military-style assault rifle to shoot through the lock of a closet in the restaurant; he was later sentenced to four years in prison.

More broadly, there’s the threat some theories pose to democratic norms, such as former President Donald Trump’s “big lie” about a stolen election, which fed into the January 6, 2021 assault on the Capitol. That one’s “a bit tricky to talk about,” D’Angelo says. The Trump team’s purported facts about the outcome of the 2020 election have been thoroughly debunked by democratic institutions, such as the court system on state and federal levels, he notes. “But when discussing and dissecting those facts in class, some students may feel as though I am professing from my own ideological perspective.”

In those cases, D’Angelo says he leans heavily on findings of scientific organizations and legitimate institutions. “I want students to be able to think for themselves, but do so by taking into account and debating what others have found out through rigorous inquiry.”

What should probably make all of us uncomfortable is disinformation and “deep fake” imagery, already proliferating, and now getting a rocket-fuel boost from artificial intelligence. Shortly after the debut of Open AI’s ChatGPT app in late 2022, more than 1,000 leading tech scientists, policy experts, and executives signed a statement warning AI carried a potential “extinction” threat that should be made “a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.” PEN America, a free-expression advocacy organization, warned in particular that “generative” AI, or systems that create their own text, audio, and image content, “has the potential to supercharge tools of deception and repression.”

“This tool is going to be the most powerful tool for spreading misinformation that has ever been on the internet,” Gordon Crovitz, a co-chief executive of NewsGuard, a company that tracks online misinformation, told the New York Times in early 2023.

Neither Arndt nor D’Angelo counts himself among the doom, however. Arndt, who also works for Silicon Valley companies as an AI trainer to help make large language models smarter and safer, is optimistic that the leading tech firms will continue building guardrails to minimize AI being used for nefarious purposes like scamming people or inventing misinformation.

Big tech, he says, “is starting to get this right.” Just as banks have begun to crush identity theft with data, he notes that a number of videos he once showed his students as examples of 9/11 conspiracy theories are no longer on YouTube, operated by Alphabet, the parent company of Google, “and they’re using mostly AI” to scrub them. “I can’t find them anymore. I can search all day long, and they’re just simply gone. I think in 10 or 20 years, between big tech companies and government regulation, it won’t be the wild west anymore.”

At the same time, “I don’t think conspiracy theories will ever go away completely, and frankly, I don’t think they should,” Arndt says. Among the “upsides” to allowing them, he says, is “they could turn out to be true,” as did the early, widely pooh-poohed theory that the Nixon White House was behind the 1972 Watergate break-in. And to “wash them completely out of the system, you’d probably have to be totalitarian, which we’re not. We live in a free-speech society. There ought to be room for legitimate questioning.” D’Angelo notes that, in order to become widespread, conspiracy theories must go public, which exposes them to critical scrutiny. “Along the lines of dealing with bullies,” that scrutiny, he believes, must be increasingly “strident” to counter the threat posed by disinformation.

At the moment, “I think our culture is cornered by conspiracy theories, and one way to get through that is to attack with a certain stridency that still adheres to journalistic principles of verification,” D’Angelo says.

“An institutional response to an intractable set of irrational propositions is a good thing,” he says.“It’s something that matters, a bulwark for democracy. If we consider, rightly so, conspiracy theories to be a drain on democracy, institutional responses are necessary.”

Still, “journalism has its work cut out for it,” and requires a citizenry armed with “news literacy and analytical tools to be effective,” says D’Angelo.

Among his students who felt better equipped after the fall term was Joe Arocho, a third-year communication studies major. Arocho says he’d begun D’Angelo’s class fairly credulous, willing to accept as true just about any assertion he came across on social media.

“I wasn’t big into news,” he says, often tuning it out as just so much noise. But the class, he says, made him realize that “you have to go back to legacy sources” to verify dubious reports on social media, and gave him a framework for doing so.

For example: After seeing videos claiming that pro-Palestinian protestors had “removed” an American flag from a pole at Harvard, Arocho says he dug deeper, and found a report in the Harvard Crimson refuting the claim; the protestors had instead cheered as the flag was lowered in the afternoon “consistent with daily routine.”

“If I feel like, ‘is the journalist giving me an opinion here?’” Arocho says, “I have to go back and fact-check that.”

Illustrations Peter Arkle

Posted on February 5, 2024