Changing the game

How the NBA’s embrace of rap music helped lead to the sport’s rapid rise..

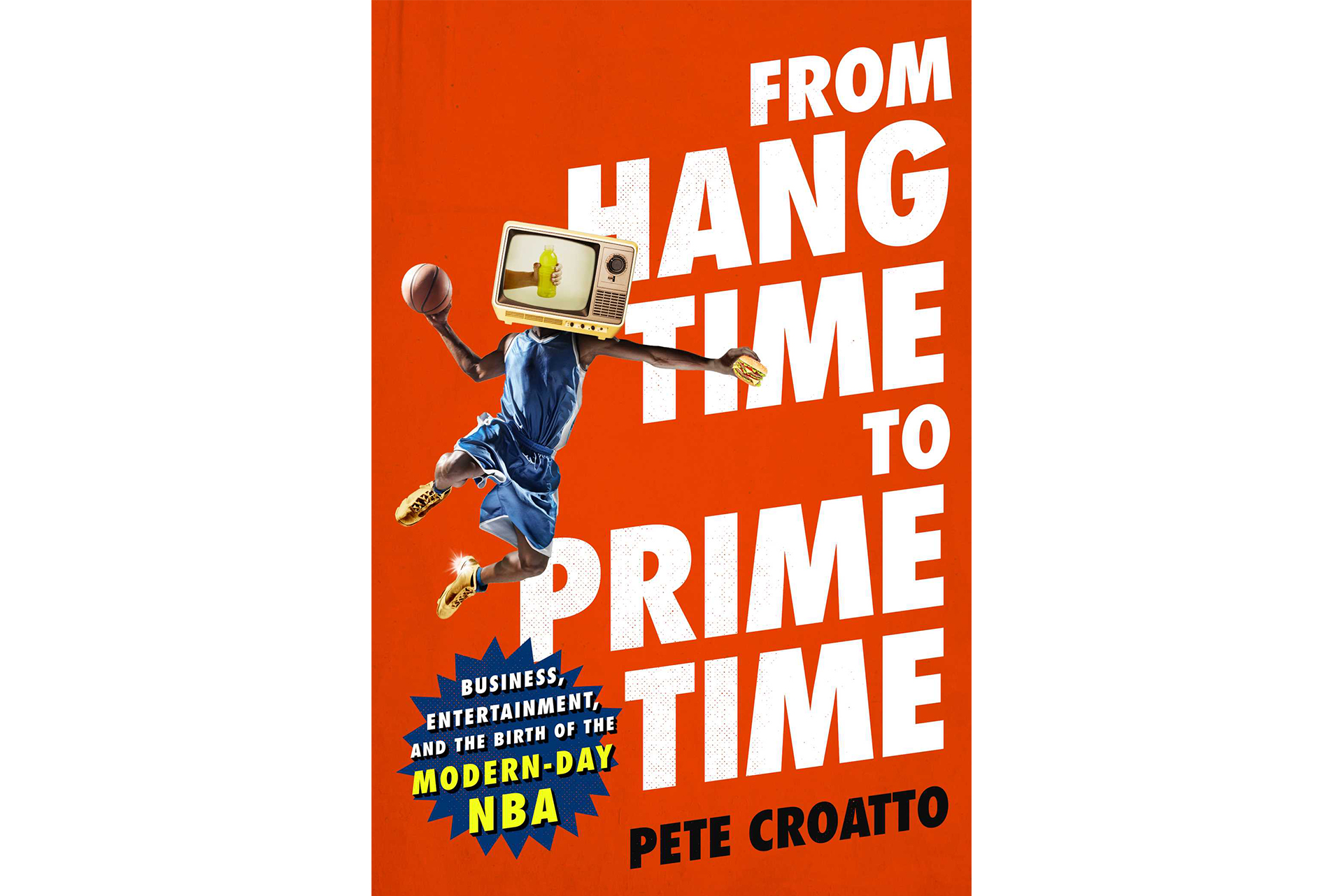

We know today’s NBA stars as much for their branded clothing and social media influence as we do for their spectacular dunks. But the league’s cultural clout didn’t just happen overnight. In his debut book, From Hang Time to Prime Time: Business, Entertainment, and the Birth of the Modern-Day NBA, excerpted here, Pete Croatto ’00 examines how the NBA’s embrace of rap music and hip-hop culture helped lead to the sport’s ascension.

Bill Stephney, a longtime executive at Def Jam Recordings, one of hip-hop’s most suc – cessful record labels, remembered Darryl Dawkins, a notable National Basketball Association player in the mid-1970s, carrying himself like a monstrous b-boy — the short hair with a part, the gold chains, the rhyming and fast talking. A decade later, as rap music got big, Dawkins’ look was no longer an anomaly in and outside of the NBA. A wave of New York–born ballplayers, like Kenny Smith, Rod Strickland, and Mark Jackson, entered the league and carried themselves and dressed like the guys from the neighborhood, the same ones who were rapping. “We didn’t look at them as hip-hop representation in the NBA, but guys from the same ’hood where the culture was,” Stephney said. The look that defined Run-DMC, the crisp Adidas shell-toes and popping sweat suits, was what the ballers at New York City’s Rucker Park would wear, Kenny Smith said. The rappers popularized it.

USA Today’s basketball editor Ron Thomas noticed, and loved, the league’s unabashed acceptance of Black culture. There were plenty of African-Americans in the NFL, but the operation felt squashed of an identity. It was so regimented. In the NBA, Thomas heard Black music in the locker room. The players would hit the clubs.

“The NBA decided that it was going to make being a Black league its brand,” said Thomas, an AfricanAmerican. “And the NBA was fine with that. I felt, without thinking about it, you were covering a Black cultural entity called the NBA.”

Christopher “Play” Martin, one half of the hip-hop group Kid ’n Play, believed athletes, rappers, and drug dealers had much in common. They came from the streets, where they were trying to find their purpose, where they celebrated together. “We all knew our plights, our struggles, our journeys to get there,” Martin said. Some members of this group, he added, wanted to trade places.

The connection between rap and basketball ran deep. For Stephney, a native New Yorker, young Black men played ball as a DJ worked turntables on the side. “I don’t know if that distinction in this area ever expressed itself,” he said. It was all part of the same experience.

As rap videos accumulated, so did employees at NBA Entertainment. The staffers grew up on MTV, said Patrick Kelleher, who joined NBA Entertainment full-time in 1990, after serving as an intern in 1989. Rap and the NBA were soul mates in commerce. The rhythm and flow of the music matched the athleticism, NBA Entertainment producer Stephen Koontz said.

The athletes were so dynamic, and the music was so new. It made sense to marry the two — especially on highlights. “You could dunk on the beat,” NBA Entertainment’s Heidi Palarz said.

Dave Zirin, the sports columnist and sports editor for The Nation, said the rap-NBA link goes back to at least the NBA Entertainment’s 1984 year-in-review video, “Pride and Passion,” where a rapper performed an original pastel-colored jam called “13 Johnsons” for a segment about the NBA players surnamed Johnson.

Thirteen men with the same last name 13 Johnsons playing the game.

It made the “Super Bowl Shuffle” sound like “Rapper’s Delight,” Zirin said.

Perhaps, but the NBA was fostering a connection with rap. Zirin also recalls Kurtis Blow’s rap classic “Basketball” being used in NBA promotions. It was appropriate. Blow considered it a theme song for basketball. He performed after games “that weren’t drawing people — Sacramento playing Washington or something. So, the game is half full. They call me in. The song was so hot, we were selling out. The games would be packed. I did that for about 20 different games. It was incredible.” Blow got to meet the players he rapped about: Isaiah Thomas, Julius Erving, George Gervin. They all hugged him like he was part of the family.

Former NBA Commissioner David Stern was fine with the NBA-rap relationship, Koontz said, “as long as we kept it in the bounds of sanity.” That meant no “Cop Killer,” no songs with outright misogyny or drug use. Into the early 1990s, most popular rap music remained benign. “There was no objection, because back then it was tamer,” said Kelleher. “We were using ‘Hip Hop Hooray.’ It wasn’t as profane as it is now.” The NBA worked with Kid ’n Play but not Dr. Dre, said longtime NBA Entertainment employee David Gavant. Controversy was a good way to alienate customers.

“They wanted to appeal to the youth, just plain and simple,” Martin said, referring to the NBA. “That was the sound of the youth. That’s what they loved. That’s what appealed to them. That was the language, the style, the culture.” Martin credited the NBA with recognizing rap’s stamina, and to choose trustworthy brands — that is, artists — that fit with the image the league wanted to promote.

“One of the things that David Stern always believed was sports as entertainment,” said Jon Miller, the cogeneral manager and vice president of NBA Entertainment. “That’s probably a cliché today; it was not a cliché then, it was a creation of that as a natural reality and a strategy. He was sort of the orchestra conductor for all that, and music was the easiest place for that to occur.”

Reprinted from FROM HANG TIME TO PRIME TIME: Business, Entertainment, and the Birth of the Modern-Day NBA by Pete Croatto with permission from Atria Books.

Cover courtesy of Atria Books.

Posted on February 11, 2021